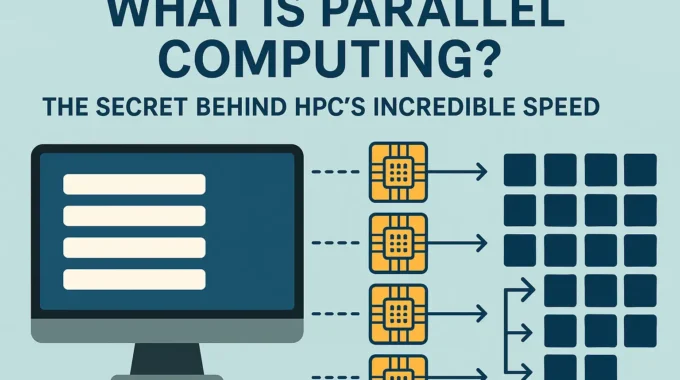

What is Parallel Computing? The Secret Behind HPC’s Incredible Speed

The insatiable demand for computational power is a defining characteristic of the 21st century. Across industries, from groundbreaking scientific research and complex engineering design to financial modeling and the artificial intelligence revolution, we are generating and processing data at an unprecedented scale. The intricate simulations required to design more efficient aircraft, discover life-saving drugs, predict global climate patterns with greater accuracy, or train sophisticated AI models that can understand and interact with the world, all share a common trait: they are immensely computationally intensive. Traditional computing approaches, primarily reliant on the sequential execution of instructions on a single processor core – a one-step-at-a-time methodology – are increasingly hitting a performance ceiling. This is not merely a slowdown but a fundamental barrier. While individual processor speeds have increased remarkably over decades (a trend famously described by Moore’s Law, which observed a doubling of transistors on a microchip roughly every two years), physical limitations such as power consumption, heat dissipation, and the inherent limits of instruction-level parallelism mean that we can no longer rely solely on making single cores faster to tackle these grand challenges. The very physics of semiconductor technology imposes constraints; as transistors shrink, quantum effects become more pronounced, and managing the heat generated by billions of closely packed components operating at high frequencies becomes an engineering feat in itself. This computational bottleneck necessitates a paradigm shift in how we approach computation, moving beyond the linear to embrace the concurrent.

The limitations of serial processing, where each operation patiently waits for the previous one to complete, have paved the way for a more powerful approach: parallel computing. This technique, which forms the very backbone of High-Performance Computing (HPC), offers a pathway to overcome the performance barriers of traditional systems. By dividing complex problems into smaller, more manageable pieces and processing them simultaneously using multiple computational resources, parallel computing unlocks speeds and capabilities that are simply unattainable with serial methods. It’s akin to transforming a single-lane country road into a multi-lane superhighway for data and calculations. This article will delve into the core concepts of parallel computing, explore its evolution from niche applications to mainstream necessity, and examine the sophisticated architectures that enable it. We will discuss different types of parallelism, strategies for scaling computational power effectively, and the mathematical laws that govern expected performance gains. Crucially, we will highlight how parallel computing in HPC is not just an academic concept but a practical, indispensable tool driving innovation across numerous real-world applications, with a special focus on its indispensable role in sophisticated engineering software like Ansys Fluent. Join us as we uncover the “secret sauce” that gives HPC its incredible speed and how MR CFD leverages this power to solve complex computational engineering challenges for its clients.

As we embark on this exploration, our first step is to clearly define parallel computing and understand its fundamental principles, contrasting it with the traditional serial model that has long been the standard.

What is Parallel Computing? Breaking Down the Core Concept

At its heart, parallel computing is a paradigm where multiple computations or the execution of processes are carried out simultaneously, effectively allowing a system to perform many different operations at the same instant in time. Instead of tackling a large, complex problem with a single processor working step-by-step (serially) through a long list of instructions, parallel computing divides the problem into smaller, often independent, parts that can be solved concurrently by multiple processing units. These units could be multiple cores within a single processor (as found in most modern desktops and laptops), multiple processors within a single, powerful HPC server, or even thousands of interconnected computers forming a vast cluster computing environment. The fundamental idea is “divide and conquer”: break down a massive, seemingly insurmountable task into manageable sub-tasks, assign each sub-task to a different “worker” (a processor core, a GPU stream processor, or an entire compute node), allow these workers to perform their calculations in parallel, and then, if necessary, combine the results from all workers to obtain the final, comprehensive solution. This simultaneous execution, this orchestration of many computational elements working in concert, is the key to achieving the dramatic speedups and enhanced problem-solving capabilities characteristic of High-Performance Computing.

Imagine trying to assemble a massive jigsaw puzzle containing tens of thousands of pieces. A single person (representing serial processing) would have to examine and place each piece one by one, a potentially monotonous and incredibly lengthy process that could take days or even weeks. Now, imagine a team of people (representing parallel processing) working on different sections of the puzzle simultaneously. Each person focuses on a smaller, more manageable portion – perhaps one works on the sky, another on a building, and a third on the landscape. Their combined effort, with each individual contributing their part of the solution in parallel, leads to a much faster completion of the entire puzzle. This analogy captures the essence of parallel computing. The “puzzle pieces” in computational terms could be different sets of data (e.g., different regions of a physical domain in a simulation), different computational tasks (e.g., calculating stress and temperature independently for a component), or different iterations of a complex loop within an algorithm. The “workers” are the CPU cores, the thousands of specialized cores within a GPU, or entire interconnected servers. The overall efficiency of this parallel approach depends on several critical factors: how well the problem can be divided into independent or nearly independent parts (its inherent “parallelizability”), the number of workers available and their individual processing power, and, crucially, how effectively these workers can communicate and coordinate their efforts, especially when results from one sub-task are needed by another. For many scientific and engineering problems, particularly those involving large datasets or complex simulations like Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD), the underlying mathematical and physical structure of the problem often lends itself remarkably well to this parallel approach, allowing for substantial performance gains.

The significance of parallel computing cannot be overstated; it has fundamentally reshaped the landscape of scientific discovery and engineering innovation. It has transformed fields that were previously constrained by insurmountable computational limits, enabling researchers and engineers to tackle problems of unprecedented scale, complexity, and fidelity. From simulating the intricate airflow around a Formula 1 car to identify minute aerodynamic improvements, to modeling the interactions of millions of atoms in the design of a new pharmaceutical compound, or processing vast datasets in genomic research to understand the genetic basis of disease, parallel computing provides the indispensable engine for discovery and innovation. It’s not just about doing things faster, although speed is a primary benefit; it’s about doing things that were previously impossible, opening up entirely new avenues of inquiry and enabling the creation of products and solutions that were once confined to the realm of imagination. As we move towards exascale computing (capable of a quintillion, or , calculations per second), understanding and effectively utilizing parallel computing principles becomes even more critical for maintaining competitive advantage and driving progress. MR CFD’s expertise in HPC is built upon a deep and practical understanding of these principles, applying them daily to deliver rapid, reliable, and accurate solutions for our clients’ most demanding CFD challenges using industry-leading tools like Ansys Fluent.

This fundamental shift from one-at-a-time processing to simultaneous computation wasn’t an overnight change or a simple upgrade. Let’s trace the historical evolution and the compelling technological drivers that led us from the era of serial processing to the parallel paradigms that now dominate the world of HPC.

From Serial to Parallel: The Evolution of Computing Paradigms

The journey of computing from its inception has been a relentless pursuit of greater speed and capability, driven by an ever-increasing appetite for solving more complex problems. Early digital computers, emerging in the mid-20th century and largely based on the Von Neumann architecture, were predominantly serial processors. They meticulously executed one instruction at a time on a single stream of data (categorized as SISD – Single Instruction, Single Data, according to Flynn’s influential Taxonomy of computer architectures). For their era, these machines were revolutionary, capable of calculations that dwarfed human speed. However, as the complexity of scientific and engineering problems grew, the inherent limitations of this strictly serial approach became increasingly apparent. For several decades, the primary way to increase performance was to increase the clock speed of the processor – essentially making it “think” faster by shortening the time it took to execute each instruction – and by adding more transistors to implement more sophisticated logic. However, by the early 2000s, this strategy began to hit fundamental physical barriers: the “power wall,” where higher clock speeds lead to exponentially increased power consumption and consequently, unmanageable heat generation within the chip, and the “instruction-level parallelism (ILP) wall,” which refers to the diminishing returns from techniques like pipelining (overlapping instruction execution stages) and superscalar execution (dispatching multiple instructions per clock cycle) within a single core. Despite clever architectural tricks, there’s a limit to how much parallelism can be extracted from a single instruction stream. It became clear that a different path, a new architectural philosophy, was needed to continue the trajectory of computational advancement.

This pressing necessity mothered the widespread adoption and mainstreaming of parallel computing architectures. While the theoretical concepts of parallelism had existed for decades – indeed, early explorations of parallel machines date back to the 1960s and 70s – and specialized vector processors (a form of SIMD – Single Instruction, Multiple Data, where a single instruction operates on multiple data elements simultaneously) had found significant use in niche scientific computing domains, the broader industry shift occurred with the advent of multi-core processors for general-purpose computing. Instead of focusing solely on making one core faster and faster, manufacturers like Intel and AMD started putting multiple complete processing cores onto a single silicon chip. This allowed even a standard desktop or laptop computer to execute multiple instruction streams (threads) simultaneously, marking a significant step towards parallel execution for everyday applications and fundamentally changing the software development landscape. In the realm of High-Performance Computing (HPC), this trend was already well underway and far more advanced. Supercomputers had long relied on massive parallelism, initially through arrays of powerful vector processors and later, more economically, through large numbers of commodity or semi-commodity processors (like those found in high-end servers) connected by specialized, high-speed networks. This led to the dominance of MIMD (Multiple Instruction, Multiple Data) architectures, where multiple autonomous processors simultaneously execute different instructions on different pieces of data, offering maximum flexibility for complex parallel tasks. This evolution was directly driven by the insatiable computational demands of fields like weather forecasting, national security applications, fundamental physics simulations, and, critically for the engineering world, Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD).

The transition was not merely a hardware evolution; it necessitated a profound paradigm shift in software development. Programs, historically written for serial execution, had to be rethought, redesigned, and often substantially rewritten to take advantage of multiple processors. This spurred the development and refinement of new programming models, parallel languages, libraries (like MPI and OpenMP), and sophisticated development tools designed to facilitate parallel programming and debugging. The rise of cluster computing, where many individual computers (nodes, often standard rack-mounted HPC server units) are linked together via a high-speed interconnect to function as a single, powerful parallel machine, further democratized access to supercomputing capabilities, bringing them within reach of smaller research groups and businesses. This architectural shift from purely serial to predominantly parallel systems underpins the incredible speeds and problem-solving capacities achieved by modern HPC systems. MR CFD has been at the forefront of leveraging this evolution, applying advanced parallel computing techniques to complex Ansys Fluent simulations, thereby enabling our clients to solve larger, more intricate fluid dynamics problems faster and with greater fidelity than ever before. The understanding of how HPC works is fundamentally tied to grasping this pivotal and ongoing transition from serial to parallel thought and execution.

The ability to execute computations in parallel is not just a conceptual advantage; it’s enabled by specific, highly engineered hardware and infrastructure components working in concert. Next, we’ll delve into the intricate architecture that forms the backbone of High-Performance Computing systems.

The Architecture Behind High-Performance Computing

High-Performance Computing (HPC) systems are sophisticated assemblies of carefully selected and integrated hardware components, meticulously designed to support massive parallel computing and handle data-intensive workloads. Understanding how HPC works necessitates a look beneath the hood at these architectural elements, which collectively deliver computational power orders of magnitude greater than that of standard desktop computers or enterprise servers. The primary building blocks of a typical HPC architecture include powerful processors (both Central Processing Units (CPUs) and, increasingly, Graphics Processing Units (GPUs) or other accelerators), a complex multi-level memory hierarchy, high-speed, low-latency network interconnects, and capacious, high-throughput storage systems. Each component plays a critical and often interdependent role, and their balanced integration is paramount to achieving optimal performance and scalability for demanding parallel applications. An imbalance, such as extremely fast processors being constantly forced to wait for data from slow memory (the “memory wall” problem) or a sluggish network unable to keep up with inter-process communication demands, can create severe bottlenecks that cripple the overall system efficiency and negate the benefits of having many processors.

Processors in modern HPC systems are typically server-grade multi-core CPUs from vendors like Intel (e.g., Xeon Scalable series) or AMD (e.g., EPYC series). These CPUs are engineered for sustained high performance, offering a high number of cores per chip (ranging from dozens to over a hundred), large on-chip caches (L1, L2, and especially L3 cache, which can be tens to hundreds of megabytes), and multiple memory channels (e.g., 8 or 12 channels per socket) to provide high aggregate memory bandwidth. Beyond CPUs, GPU acceleration has become a cornerstone of contemporary HPC design. GPUs, originally designed for the massively parallel task of rendering graphics, possess thousands of smaller, simpler cores (often called stream processors or CUDA cores). This architecture makes them exceptionally efficient at performing the same operation on large blocks of data simultaneously (a form of data parallelism known as SIMT – Single Instruction, Multiple Threads). This makes GPUs ideal for certain types of scientific and engineering calculations prevalent in fields like CFD, molecular dynamics, and deep learning, often providing significant speedups for amenable algorithms. The memory hierarchy within an HPC server node is also critical and more complex than in standard systems. This includes the aforementioned fast on-chip caches, large amounts of main system memory (RAM, often hundreds of gigabytes to terabytes per node), and careful consideration of Non-Uniform Memory Access (NUMA) characteristics. In NUMA systems, each CPU socket has its own directly attached local memory, and accessing this local memory is faster than accessing memory attached to another CPU socket on the same node. Parallel programs must be NUMA-aware to optimize data placement and access patterns. In a distributed-memory cluster computing environment, which is the most common HPC setup, each node has its own independent memory address space, and data sharing between nodes occurs explicitly over the network.

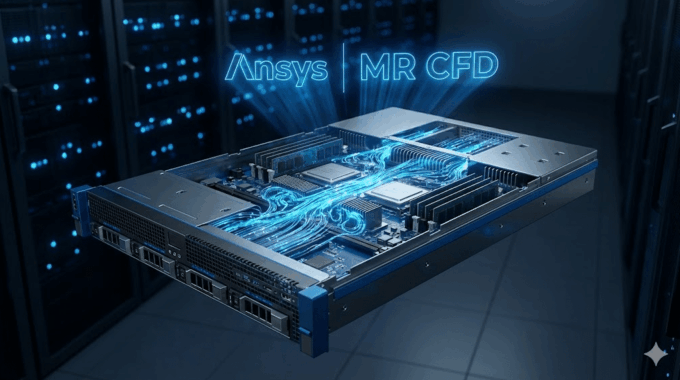

The network interconnect is arguably one of the most crucial components differentiating HPC clusters from standard networked computers or less demanding server farms. While office networks typically use standard Ethernet, HPC clusters employ specialized high-bandwidth, low-latency interconnects like InfiniBand (e.g., NDR, XDR generations) or high-speed Ethernet variants incorporating RDMA (Remote Direct Memory Access) capabilities (like RoCE – RDMA over Converged Ethernet or iWARP). These advanced interconnects allow for extremely rapid communication and synchronization between the hundreds or even thousands of nodes in a large cluster, which is absolutely essential for parallel algorithms that require frequent and voluminous data exchange between processes. The latency (the time delay for a message to start its journey) can be in the order of microseconds or less, and bandwidth (the data transfer rate) can be hundreds of gigabits per second per link. The topology of this network (e.g., fat-tree, dragonfly, torus, or custom designs) is also carefully engineered to provide high bisection bandwidth (a measure of the network’s capacity to handle all-to-all communication patterns) and fault tolerance, ensuring that communication bottlenecks are minimized even under heavy load. Finally, HPC systems rely on high-performance parallel storage systems (e.g., Lustre, GPFS/Spectrum Scale, BeeGFS). These file systems are designed to allow many compute nodes to read and write data concurrently at very high aggregate speeds (terabytes per second), which is vital for handling the massive datasets generated by large simulations or used as input to them. MR CFD’s expertise extends to designing, deploying, and utilizing HPC environments where these architectural components are optimally configured and balanced for demanding Ansys Fluent simulations, ensuring that our clients benefit from true high-performance computing capabilities and not just a collection of fast processors.

With this understanding of the underlying hardware infrastructure that makes large-scale parallelism possible, we can now explore the different forms that parallelism can take at a more granular, algorithmic level.

Types of Parallelism: Task, Data, and Instruction-Level

Parallel computing is not a monolithic concept; it manifests in various forms, each suited to different types of problems, algorithmic structures, and hardware capabilities. Understanding these different types of parallelism—primarily Instruction-Level Parallelism (ILP), Task Parallelism, and Data Parallelism—is crucial for designing efficient parallel algorithms, for software developers creating parallel applications, and for users appreciating how sophisticated software like Ansys Fluent leverages the diverse capabilities of High-Performance Computing (HPC) systems. These types of parallelism are not mutually exclusive; they can often coexist and be exploited simultaneously within a complex application running on an HPC server to maximize performance.

Instruction-Level Parallelism (ILP) is a form of parallelism exploited at the lowest level of computation, typically within a single CPU core by the processor hardware itself. Modern processors employ several techniques to execute multiple instructions from a single program thread concurrently. Pipelining, for instance, breaks down the execution of an instruction into several stages (fetch, decode, execute, memory access, write back). By overlapping these stages for different instructions, the processor can have multiple instructions in different stages of execution simultaneously, much like an assembly line. Superscalar execution takes this further by having multiple independent execution units within a core (e.g., multiple integer units, floating-point units), allowing the processor to issue and execute more than one instruction per clock cycle if they are independent. Out-of-order execution allows the processor to reorder instructions to find more opportunities for ILP, executing instructions as soon as their operands are ready, rather than strictly in program order. ILP is largely handled automatically by the processor hardware and sophisticated compiler optimizations, without explicit intervention from the programmer of a high-level application. While critically important for achieving good single-core performance, the practical gains from ILP have limitations and diminishing returns, which was a key driving factor for the industry’s shift towards multi-core and many-core architectures to exploit other, more explicit forms of parallelism.

Task Parallelism focuses on distributing different, distinct tasks or functions across multiple processors or cores to be executed concurrently. In this model, different computational units work on entirely different operations, often on different sets of data. For example, in a complex multi-physics simulation, one set of cores might be responsible for solving the fluid dynamics equations for a component, while another set of cores concurrently handles the structural mechanics calculations for the same component, and perhaps a third set performs real-time visualization or data analysis tasks. If these tasks are largely independent or have well-defined, infrequent points of interaction and data exchange, they can proceed efficiently in parallel. A web server handling multiple distinct client requests simultaneously is another classic example of task parallelism, where each request is a separate task. The degree of speedup achievable through task parallelism depends heavily on the number of genuinely independent tasks available in the application, the computational load of each task (good load balance is important), and the overhead associated with managing and synchronizing these tasks.

Data Parallelism is perhaps the most common and impactful type of parallelism in scientific and engineering computing, including the vast majority of CFD applications. It involves performing the same operation or sequence of operations concurrently on different elements of a large dataset. Each processing unit executes the same instruction sequence but on its own distinct partition or subset of the data. For instance, if you need to add a constant value to every element in a very large array, a data-parallel approach would assign different segments of the array to different cores, and each core would perform the identical addition operation on its assigned segment simultaneously. This is often referred to as SPMD (Single Program, Multiple Data), a widely used programming model where all parallel processes execute the same program code but operate on different portions of the shared data. Ansys Fluent, when solving equations on a large computational mesh, heavily utilizes data parallelism by decomposing the mesh (the data) into many sub-domains and having each core (or process) solve the same set of governing equations for its assigned portion of the mesh. GPU acceleration particularly excels at fine-grained data parallelism due to the thousands of specialized cores designed for such SIMT (Single Instruction, Multiple Threads) operations, making them highly effective for matrix operations, stencil computations, and other regular data-intensive tasks found in CFD solvers. MR CFD leverages this by ensuring hpc for ansys fluent environments are meticulously optimized for the predominantly data-parallel nature of advanced CFD simulations.

Here are simple conceptual code illustrations to further clarify these types:

- Task Parallelism (Conceptual Pseudocode for a hypothetical coupled simulation):

BEGIN_PARALLEL_TASKS TASK A: // Core group 1: Solve fluid dynamics equations Initialize_Fluid_Solver() FOR timestep = 1 TO N_timesteps Advance_Fluid_Solution() Send_Pressure_Loads_To_Structure_Solver() Receive_Boundary_Displacements_From_Structure_Solver() END_FOR TASK B: // Core group 2: Solve structural mechanics equations Initialize_Structure_Solver() FOR timestep = 1 TO N_timesteps Receive_Pressure_Loads_From_Fluid_Solver() Advance_Structure_Solution() Send_Boundary_Displacements_To_Fluid_Solver() END_FOR TASK C: // Core group 3: Perform in-situ data analysis and visualization Initialize_Analysis_Engine() FOR timestep = 1 TO N_timesteps IF (timestep MOD analysis_frequency == 0) THEN Request_Data_From_Solvers() Perform_Analysis() Update_Visualization_Stream() END_IF END_FOR END_PARALLEL_TASKS Data Parallelism (Conceptual Pseudocode for applying a filter to an image, where each pixel is processed independently):

// Image has Width x Height pixels // P_cores available for processing // Each core processes a horizontal strip of the image FOR core_idx = 0 TO P_cores - 1 IN_PARALLEL // Determine the range of rows this core will process start_row = core_idx * (Height / P_cores) end_row = (core_idx + 1) * (Height / P_cores) - 1 FOR y = start_row TO end_row FOR x = 0 TO Width - 1 // Apply a filter operation (e.g., blur, sharpen) to Image[x][y] // This operation is the same for all pixels, but applied to different data new_pixel_value = Apply_Filter(Image[x][y], neighborhood_pixels) Output_Image[x][y] = new_pixel_value END_FOR END_FOR END_FOR

These different forms of parallelism provide a versatile toolkit for accelerating a wide range of computations. The choice of how to build and configure systems that effectively exploit these parallel capabilities leads to different strategic approaches to scaling computational resources.

6. Scaling Up vs. Scaling Out: Strategic Approaches to HPC

When the demand for computational power outstrips the capabilities of an existing system, organizations face a fundamental decision on how to increase their capacity to meet growing needs. In the context of High-Performance Computing (HPC), two primary strategic approaches emerge for enhancing computational throughput: scaling up (often referred to as vertical scaling) and scaling out (also known as horizontal scaling). Each strategy has distinct implications for system architecture, initial and ongoing costs, day-to-day manageability, fault tolerance, and the types of parallel computing problems it best supports. Understanding these differences is crucial for designing or selecting an HPC solution that aligns with specific workload requirements, such as those for demanding, memory-intensive Ansys Fluent simulations, and for making informed long-term investment decisions.

Scaling Up (Vertical Scaling) involves increasing the resources of a single machine or a tightly coupled system that behaves like one. This typically means upgrading to a more powerful HPC server with faster or more numerous CPUs (sockets), adding significantly more Random Access Memory (RAM), incorporating more powerful GPUs or other accelerators, or expanding its internal high-speed storage capacity. The quintessential example of a scale-up system is a large Symmetric Multiprocessing (SMP) or Non-Uniform Memory Access (NUMA) server where all processors have direct access to a common global memory pool, albeit with varying access latencies in NUMA systems. The primary advantage of this approach is that, for applications designed for shared-memory parallelism (like those utilizing OpenMP or Pthreads), the programming model can be considerably simpler as all threads have direct, low-latency access to the same data structures in memory, avoiding the complexities of explicit message passing. However, scaling up has inherent physical and economic limits. The cost of high-end, monolithic systems often increases exponentially with performance improvements; doubling the power doesn’t just double the cost, it can be much more. Furthermore, there’s an ultimate ceiling to how powerful a single machine can become due to constraints in processor technology, memory bus bandwidth, power delivery, and heat dissipation within a single chassis. While effective to a certain point for specific workloads, relying solely on scaling up is often not the most cost-effective or scalable long-term solution for the massive and ever-growing computational demands of modern HPC.

Scaling Out (Horizontal Scaling), in stark contrast, involves adding more individual machines (commonly referred to as nodes) to a distributed system, typically forming a cluster computing environment. Each node is a self-contained computer (often a standard or semi-custom HPC server) with its own processors, its own local memory, and often its own local storage, all interconnected by a specialized, high-speed network fabric. This is the dominant paradigm in modern HPC and forms the basis of most of the world’s largest supercomputers. The primary advantage of scaling out is its virtually limitless scalability in aggregate computational power and memory capacity; one can, in principle, keep adding more nodes to the cluster to handle larger problems or more concurrent users. It’s generally more cost-effective to build an extremely powerful system from many commodity or semi-commodity nodes than from a single, extremely high-end monolithic machine, offering a better price-to-performance ratio at large scales. However, scaling out typically relies on distributed-memory parallelism (using programming models like the Message Passing Interface – MPI), where processes running on different nodes have their own private memory spaces and communicate by explicitly passing messages over the network. This can introduce greater programming complexity and makes the performance (both latency and bandwidth) of the network interconnect critically important to overall application performance and scalability. Most large-scale parallel computing in HPC, including the methods by which Ansys Fluent achieves massive speedups for complex simulations, is based on this scale-out model, distributing both data and computation across many cooperating nodes. MR CFD designs and manages HPC solutions that effectively leverage horizontal scaling to provide clients with the robust and scalable power needed for their complex CFD simulations, ensuring that resources can grow with their computational ambitions.

| Feature | Scaling Up (Vertical Scaling) | Scaling Out (Horizontal Scaling) |

| Method | Increase resources (CPU, RAM, GPU) of a single server/system | Add more individual servers (nodes) to a cluster |

| Architecture | Shared Memory (typically SMP or large NUMA systems) | Distributed Memory (typically a cluster of nodes) |

| Max Scale | Limited by single machine technology and cost | Virtually unlimited in principle, very high scalability possible |

| Cost | High cost for high-end systems, can grow exponentially | More cost-effective for achieving massive scale, better price/perf |

| Programming Model | Simpler for shared memory models (e.g., OpenMP, Pthreads) | More complex for distributed memory models (e.g., MPI) |

| Primary Bottleneck | Single system limits (CPU speed, memory bus bandwidth, I/O) | Network interconnect performance, communication overhead, latency |

| Management | Simpler (managing one or a few large systems) | More complex (managing many nodes, cluster software stack) |

| Fault Tolerance | Single point of failure can be significant | Can be designed for higher fault tolerance (node failure) |

| Example | Large SMP server, Mainframe, high-end workstation (to a degree) | HPC Cluster, Beowulf cluster, cloud compute instances |

The choice between scaling up and scaling out (or, increasingly, a hybrid approach that combines elements of both) depends heavily on the specific application workload characteristics (e.g., memory access patterns, communication intensity), budget constraints, existing infrastructure, and long-term strategic goals. As we scale these systems using either approach, it’s important to have a robust way to predict and understand the performance gains we can realistically expect. This brings us to the theoretical frameworks that govern the limits and potentials of parallel speedup.

7. The Mathematics of Speedup: Amdahl’s Law and Gustafson’s Law

Achieving optimal performance in parallel computing is not simply a matter of throwing an ever-increasing number of processors at a problem and expecting a proportional decrease in execution time. The actual speedup obtained is governed by fundamental theoretical principles, most notably Amdahl’s Law and Gustafson’s Law (also known as Gustafson-Barsis’s Law). These laws provide mathematical frameworks for understanding and predicting the potential performance gains from parallelization and, just as importantly, highlight the inherent limitations and opportunities in High-Performance Computing (HPC). They are crucial for setting realistic expectations for application scaling, for guiding efforts in optimizing parallel applications (including complex software like Ansys Fluent running on an HPC server), and for making informed decisions about hardware investments. Understanding these concepts helps explain the often-observed phenomenon where doubling the number of cores doesn’t always halve the execution time, especially as systems scale to very large processor counts.

Amdahl’s Law, formulated by computer architect Gene Amdahl in 1967, focuses on the scenario of a fixed-size problem, often referred to as strong scaling (i.e., how much faster can we solve the same problem by using more processors?). It states that the maximum speedup achievable by parallelizing a task is ultimately limited by the portion of the task that must be performed serially – that is, the part of the code that, for algorithmic or dependency reasons, cannot be broken down and executed in parallel. If S is the fraction of the program’s total execution time that is inherently serial (cannot be parallelized) and P is the fraction that can be parallelized (so S + P = 1), then the theoretical speedup Speedup(N) using N processors is given by the formula:

Speedup(N) = 1 / (S + (P/N))

As N (the number of processors) approaches infinity, the term P/N (the time spent on the parallelizable part) approaches zero. Consequently, the speedup becomes limited to 1/S. This has profound implications: if, for example, 10% of a program’s execution time is serial (S = 0.1), then even with an infinite number of processors, the maximum possible speedup is 1/0.1 = 10x. If 25% is serial (S = 0.25), the maximum speedup is capped at 4x. Amdahl’s Law underscores the critical importance of minimizing the serial fraction of code to achieve good scalability, as this serial component becomes the dominant bottleneck at high processor counts. For CFD simulations, this serial portion might include tasks like initial problem setup, certain global data aggregations, some I/O operations (like reading a large mesh file serially), or specific algorithmic steps that are inherently sequential.

Gustafson’s Law (or Gustafson-Barsis’s Law), proposed by John Gustafson and Edwin Barsis in 1988, offers a different and often more optimistic perspective, particularly relevant to large-scale HPC scenarios. This law considers a scenario where the problem size is allowed to increase proportionally with the number of available processors, a concept known as weak scaling (i.e., how much larger a problem can we solve in the same amount of time by using more processors?). Gustafson argued that as computational power increases, users don’t just solve the same small problems faster; they tend to tackle larger, more complex, or higher-fidelity problems, effectively keeping the parallel execution time per processor roughly constant. His law is formulated for this kind of scaled speedup. If s represents the time spent on serial parts of the code and p represents the time spent on parallelizable parts when run on a single processor, then for a problem where the parallel workload scales by a factor of N when using N processors, the scaled speedup can be expressed as:

Speedup_scaled(N) = (s + N*p) / (s + p) = s + N*p (if normalized such that s+p=1 on a single processor, then Speedup_scaled(N) = S + N*(1-S) = N – S*(N-1), where S is the serial fraction of the parallelized code’s runtime on N processors). This law suggests that for problems with a high degree of inherent parallelism and where the problem size can be effectively scaled (e.g., by refining a mesh or increasing the number of particles in a simulation), it’s possible to achieve near-linear speedups relative to the scaled problem size. This is often observed in HPC for Ansys Fluent when users increase mesh resolution (thus increasing the total work) as they move to larger cluster computing systems, aiming to maintain a similar wall-clock time per simulation but with much greater detail. MR CFD considers both Amdahl’s and Gustafson’s laws when advising clients on scaling strategies and performance expectations, as real-world application performance is often a complex interplay influenced by factors described by both theoretical limits.

These laws are not contradictory but rather describe different aspects of parallel performance. Amdahl’s Law highlights the challenge of the irreducible serial component in speeding up a fixed-size problem, while Gustafson’s Law emphasizes the potential to solve much larger problems efficiently by scaling both the problem and the machine. The art of HPC and parallel algorithm design lies in creating applications that have a very small serial fraction (S) and can effectively scale their parallelizable workload (P) to take full advantage of increasing numbers of processors.

With these theoretical underpinnings that help us quantify and understand the limits and potentials of parallel execution, let’s explore the diverse real-world applications where parallel computing in HPC is making a significant and often transformative impact.

Real-World HPC Applications: Where Parallel Computing Shines

The transformative power of High-Performance Computing (HPC), fueled by the engine of parallel computing, is not confined to theoretical exercises or niche academic pursuits; it is a pervasive and increasingly indispensable force driving innovation and discovery across a vast spectrum of industries and scientific disciplines. The ability to process massive datasets, simulate highly complex phenomena, and perform intricate calculations at unprecedented speeds has opened new frontiers, enabled the solution of problems previously considered intractable, and accelerated the pace of research and development globally. Understanding how HPC works in these diverse contexts reveals its profound impact on our daily lives, economic competitiveness, national security, and fundamental scientific advancement. From designing safer and more fuel-efficient transportation systems to forecasting devastating hurricanes with greater lead time, and from unraveling the mysteries of the universe to developing personalized medicine, parallel computing in HPC is an essential tool for progress in the modern era.

In scientific research, HPC is fundamental to nearly every major field of inquiry. Climate scientists and meteorologists use some of the world’s largest supercomputers to run sophisticated global climate models and numerical weather prediction systems. These models simulate complex atmospheric and oceanic dynamics, incorporating vast amounts of observational data, to predict long-term climate change scenarios, improve the accuracy of short-term weather forecasts, and provide early warnings for extreme weather events like tornadoes and tsunamis. Astrophysicists perform massive N-body simulations to model the evolution of galaxies, the formation of stars and planetary systems, and the large-scale structure of the universe, often involving billions of interacting particles over cosmological timescales. In particle physics, experiments at facilities like the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) at CERN generate petabytes of raw data from particle collisions. This data requires enormous parallel computing resources for filtering, reconstruction, and analysis, leading to profound discoveries about fundamental particles and the forces that govern their interactions, such as the discovery of the Higgs boson. Furthermore, genomics and bioinformatics rely heavily on HPC for tasks like sequencing and assembling entire genomes, identifying genetic variations associated with diseases, simulating protein folding and drug interactions (critical for rational drug discovery and design), and constructing complex phylogenetic trees to understand evolutionary relationships, thereby accelerating our understanding of life itself at its most fundamental level.

The engineering world has been comprehensively revolutionized by the capabilities of HPC. Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD), a core area of expertise for MR CFD, allows engineers to simulate intricate fluid flow patterns and heat transfer phenomena for a wide array of applications. These range from optimizing the aerodynamic efficiency of aircraft wings and automobile bodies to reduce drag and fuel consumption, to designing more efficient and cleaner combustion engines and gas turbines, and to modeling the complex mixing processes within chemical reactors for improved yield and safety. Similarly, Finite Element Analysis (FEA) performed on HPC systems enables the detailed simulation of structural stresses, deformations, vibrations, and thermal responses in mechanical components, bridges, buildings, and advanced materials, ensuring structural integrity, optimizing material usage, and predicting product lifespan under various operating conditions. The automotive industry, for example, uses HPC extensively for virtual crash simulations, allowing engineers to test numerous safety designs and vehicle structures digitally, significantly reducing the need for expensive and time-consuming physical prototypes while leading to demonstrably safer vehicles. In the energy sector, reservoir modeling on HPC clusters helps geophysicists and petroleum engineers analyze seismic data and simulate fluid flow through porous rock formations to optimize the extraction of oil and gas resources. Simultaneously, HPC simulations are crucial for designing more efficient wind turbines by modeling airflow over blades and entire wind farms, and for developing next-generation solar energy systems and battery technologies. Even the financial industry, often perceived as distinct from traditional scientific computing, leverages HPC for complex quantitative modeling, algorithmic high-frequency trading, comprehensive risk analysis (e.g., Value at Risk calculations for large portfolios), and real-time fraud detection, processing and analyzing vast streams of market data with extremely low latency requirements. The common thread across all these diverse and impactful applications is the fundamental need to solve computationally intensive problems that benefit immensely from the divide-and-conquer strategy and the massive concurrency offered by parallel computing.

This broad impact underscores the versatility and critical importance of HPC in the modern world. Now, let’s focus on a specific, highly impactful application area within the engineering domain: the powerful and synergistic computational partnership between the Ansys Fluent software and HPC environments.

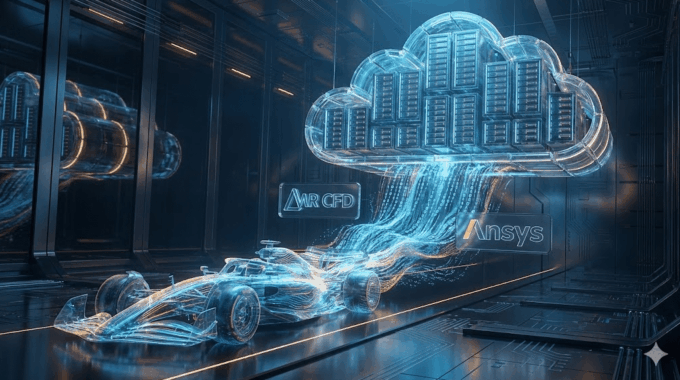

ANSYS Fluent and HPC: A Perfect Computational Partnership

ANSYS Fluent, a leading and widely adopted software suite for Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD), stands as a prime example of an application that not only benefits from but often fundamentally thrives in a High-Performance Computing (HPC) environment. The complex physics, intricate multi-scale geometries, and the sheer number of degrees of freedom involved in modern industrial and research-grade CFD simulations inherently demand massive computational resources. This makes parallel computing not just a beneficial accelerator but frequently an essential prerequisite for achieving timely, accurate, and economically viable results. The synergistic partnership between Ansys Fluent and HPC allows engineers and researchers to push the boundaries of simulation fidelity, tackle problems of unprecedented scale and complexity (such as simulating an entire engine or a full-scale chemical plant), and dramatically accelerate the design, analysis, and optimization process across a multitude of industries including aerospace, automotive, energy, manufacturing, and biomedical engineering. Understanding this powerful synergy is key to appreciating why investing in or accessing dedicated HPC for Ansys Fluent is a strategic imperative for organizations that are serious about leveraging advanced computational engineering to gain a competitive edge.

The core reasons Ansys Fluent so heavily demands HPC capabilities lie in the inherent nature of the CFD problems it is designed to solve. These simulations routinely involve:

- Large and Complex Meshes: Accurately capturing the intricate geometric details of real-world objects (e.g., the subtle curves of an aircraft wing, the complex internal passages of a turbocharger, the porous structure of a catalytic converter, or the detailed vasculature in a biomedical device) requires discretizing the computational domain into millions, tens of millions, or even billions of individual cells or elements. Storing the geometric information and multiple solution variables (pressure, velocity components, temperature, species concentrations, turbulence quantities, etc.) for each of these cells requires substantial memory footprints, often far exceeding the capacity of even high-end workstations. Processing these vast datasets iteratively also demands immense computational effort.

- Sophisticated and Coupled Physics: Modern engineering simulations rarely involve just simple fluid flow. They often incorporate advanced turbulence models (like Reynolds-Averaged Navier-Stokes (RANS), Large Eddy Simulation (LES), or Detached Eddy Simulation (DES)), multiphase flows (e.g., liquid-gas, solid-liquid), intricate heat transfer mechanisms (conduction, convection, radiation), complex chemical reactions (as in combustion or chemical reactors), aeroacoustics for noise prediction, and fluid-structure interaction (FSI) where fluid forces cause structural deformation which in turn affects the flow. Each additional physical model introduces more equations to be solved per cell, more variables to be stored, and often tighter coupling between different parts of the system, all of which significantly escalate the computational cost and complexity.

- Transient (Time-Dependent) Simulations: Many real-world fluid phenomena are inherently unsteady or transient, meaning the flow field changes significantly over time (e.g., vortex shedding behind a cylinder, the operation of a reciprocating engine, the filling of a mold). Simulating these transient phenomena accurately requires solving the governing equations at many small, discrete time steps, often thousands or even millions of them. This multiplies the total computational workload dramatically compared to steady-state simulations, which seek a single, time-invariant solution.

Ansys Fluent is architected from the ground up to effectively leverage parallel computing to address these challenges. It employs sophisticated domain decomposition techniques (like METIS, K-way, or Principal Axes partitioning) to intelligently partition the computational mesh across multiple processor cores. These cores can reside within a single multi-core HPC server (exploiting shared-memory parallelism via threading) or, more commonly for large problems, be distributed across many interconnected nodes in a cluster computing environment (exploiting distributed-memory parallelism). Fluent utilizes the Message Passing Interface (MPI) standard – the lingua franca of distributed HPC – for robust and efficient communication and data exchange between these distributed processes, ensuring that all parts of the simulation work in concert to produce a globally consistent solution. This inherent parallelism allows Fluent to scale effectively, distributing both the immense computational load and the substantial memory requirements across many processing elements, thereby drastically reducing solution times from weeks or months to days or even hours.

The benefits of this Fluent-HPC partnership are transformative for engineering workflows. A complex simulation that might take an impractically long time (or be impossible due to memory limitations) on a high-end workstation can often be completed in a matter of hours or overnight on an appropriately sized and configured HPC cluster. This dramatic speedup enables engineers to perform more design iterations, conduct comprehensive parametric studies to explore the effect of different design variables, undertake rigorous optimization workflows, and investigate more complex physical scenarios that would be prohibitive on lesser hardware. For organizations looking to maximize their CFD capabilities and extract the most value from their simulation investments, MR CFD provides specialized hpc for ansys solutions, readily accessible via our dedicated portal at https://portal.mr-cfd.com/hpc. We possess the expertise to help clients configure and optimize Ansys Fluent on powerful HPC infrastructure, ensuring they can tackle their most challenging fluid dynamics problems with confidence, speed, and enhanced accuracy. For instance, simulating the detailed combustion process within a modern gas turbine engine, involving intricate fuel injection systems, turbulent reacting flow, multiple chemical species, and intense heat transfer, is a quintessential task that truly showcases the formidable power of Ansys Fluent when coupled with robust parallel computing in HPC. Without this partnership, such high-fidelity analyses would remain out of reach for most practical engineering timelines.

To achieve this “perfect computational partnership” and extract maximum performance, specific hardware considerations are paramount. Next, we will outline the key hardware requirements that enable Ansys Fluent to perform optimally on HPC systems.

Hardware Requirements for Optimal ANSYS Fluent Performance

Achieving optimal performance and scalability with Ansys Fluent in a High-Performance Computing (HPC) environment hinges on a well-balanced and appropriately specified hardware infrastructure. Simply having access to an HPC cluster is not enough; the specific characteristics of the Central Processing Units (CPUs), the memory subsystem (capacity, bandwidth, and latency), the network interconnect fabric, and the storage solutions all play crucial and often interdependent roles in determining how efficiently Fluent simulations will run and scale. For organizations investing in dedicated hpc for ansys fluent infrastructure, or for those utilizing cloud-based HPC resources, a clear understanding of these hardware requirements is essential for maximizing return on investment and ensuring that raw computational power translates directly into faster, more accurate, and more insightful simulation results. An imbalanced system, where one component (e.g., slow memory or a congested network) creates a persistent bottleneck, can severely limit the effectiveness of even the most powerful processors and lead to frustratingly suboptimal performance.

CPU (Central Processing Unit): For Ansys Fluent, the choice of CPU involves a careful balance of several factors: core count, clock speed (frequency), Instructions Per Clock (IPC) which reflects architectural efficiency, and the size and speed of on-chip caches (L1, L2, and particularly L3). While a higher core count directly contributes to the parallel computing capability available for domain decomposition, the per-core performance remains highly important, especially for those parts of the Fluent code that may not scale perfectly linearly or for the main solver processes running on each core. High clock speeds and strong IPC contribute to faster execution of serial code sections within the solver and quicker processing of computational kernels within each parallel task. Large L3 caches (often tens to hundreds of megabytes in server-grade CPUs) are particularly beneficial as they can significantly reduce effective memory latency by keeping frequently accessed data (like parts of the mesh or solver matrices) closer to the processing cores, minimizing trips to slower main memory. Both Intel Xeon Scalable processors and AMD EPYC series CPUs are widely used and well-regarded in HPC servers for demanding Fluent workloads, each offering different strengths in terms of core density, price-performance ratios, memory channel support, and specific architectural features that might favor certain types of computations.

Memory (RAM – Random Access Memory): CFD simulations, particularly those executed with Ansys Fluent, are notoriously memory-intensive. The primary driver for memory capacity is the mesh size; larger and more complex meshes inherently require more RAM to store cell data, connectivity information, and solution variables. A critical metric often considered is the amount of RAM available per core. For Fluent, a common general recommendation is to have at least 4GB to 8GB of RAM per physical CPU core allocated to the simulation. However, this can easily increase to 16GB/core, 32GB/core, or even more for simulations involving very large cell counts (hundreds of millions or billions), complex physics models (e.g., multiphase models with many phases, detailed chemical kinetics with numerous species, or Large Eddy Simulations requiring fine resolution), or when using certain solver features that have higher memory footprints. Beyond sheer capacity, memory bandwidth is equally crucial, if not more so for many CFD workloads. CPUs with more memory channels (e.g., 8-channel DDR4/DDR5 or 12-channel configurations found in modern server CPUs) can deliver data to the cores much faster, preventing them from becoming “starved” for data and sitting idle. Fast RAM speeds (e.g., DDR4-3200, DDR5-4800 or higher) also contribute to higher bandwidth. Non-Uniform Memory Access (NUMA) awareness in how Fluent processes are mapped to cores and memory banks is important; ensuring that processes primarily access memory local to their CPU socket minimizes latency and maximizes effective bandwidth.

Network Interconnect: For multi-node Ansys Fluent simulations, which are standard for any reasonably sized problem, the performance of the network interconnect is paramount for achieving good scalability and overall efficiency. This is the specialized fabric that allows the different HPC server nodes within a cluster computing environment to communicate and exchange data rapidly and reliably. This data exchange primarily involves boundary information for “halo” or “ghost” cells between decomposed mesh partitions, as well as collective operations for global reductions or synchronizations. Both low latency (the time it takes for a small message to start transferring and arrive at its destination) and high bandwidth (the rate at which large volumes of data can be transferred) are critical. InfiniBand (with its various generations like HDR, NDR, and the upcoming XDR) is often the preferred interconnect for demanding HPC workloads, including Fluent, due to its very low latency (often in the microsecond or sub-microsecond range) and very high bidirectional bandwidth (hundreds of Gigabits per second per link). High-speed Ethernet (typically 100Gbps, 200Gbps, or faster) enhanced with RDMA (Remote Direct Memory Access) capabilities, such as RoCE (RDMA over Converged Ethernet) or iWARP, is also a viable and increasingly common option, especially as its performance characteristics continue to improve. A slow, congested, or high-latency network will severely limit how well Fluent can scale beyond a single node, as processes will spend an excessive and increasing proportion of their time waiting for data from other nodes rather than performing useful computation.

Storage: While not always directly involved in the iterative solving process as intensively as CPU and memory, the storage subsystem plays a vital role in the overall workflow efficiency and productivity for Ansys Fluent users. This includes enabling fast loading of large input mesh files (which can be tens or hundreds of gigabytes), facilitating quick writing of solution data files (especially for transient simulations that generate output at many time steps or for frequent checkpointing of long-running jobs), and supporting efficient post-processing and visualization of the results. For on-premises HPC clusters, a parallel file system (such as Lustre, BeeGFS, IBM Spectrum Scale/GPFS, or WekaIO) is typically used. These advanced file systems are designed to provide concurrent, high-throughput access from all compute nodes in the cluster, avoiding the I/O bottlenecks that would occur with traditional Network Attached Storage (NAS) or Storage Area Network (SAN) solutions not optimized for parallel access. Fast local Non-Volatile Memory Express (NVMe) SSDs on individual compute nodes can also be beneficial for storing temporary data, scratch space for the solver, or for accelerating I/O for specific parts of the workflow if managed effectively. MR CFD meticulously designs its HPC offerings to ensure these critical hardware components are not only individually powerful but also well-balanced and optimally configured to provide peak, sustained Ansys Fluent performance for our clients.

| Component | Key Consideration for Ansys Fluent | Typical HPC Specification Examples |

| CPU | High clock speed, good IPC, high core count per socket, large L3 cache, strong floating-point performance | Intel Xeon Scalable (e.g., Sapphire Rapids, Emerald Rapids), AMD EPYC (e.g., Genoa, Bergamo) |

| Memory (RAM) | High capacity per core (8-16GB+ recommended, up to 32GB+ for very large models), high bandwidth, multiple channels per CPU | DDR4-3200 / DDR5-4800/5600+, 8 to 12 memory channels per CPU socket |

| Network | Extremely low latency (microseconds), very high bandwidth (100Gbps to 400Gbps+ per link), efficient MPI support | InfiniBand (HDR, NDR, XDR), High-Speed Ethernet with RDMA (e.g., 200G/400G RoCE) |

| Storage | High aggregate throughput (GB/s to TB/s), concurrent access for large files, low latency for metadata operations | Parallel File Systems (Lustre, BeeGFS, Spectrum Scale), All-Flash Arrays, NVMe-based solutions |

Understanding these hardware prerequisites is the first crucial step in building or selecting an effective HPC platform for Ansys Fluent. Next, we will explore how Ansys Fluent’s performance actually scales across different computing environments, from individual workstations to large-scale supercomputers, and what factors influence this scalability.

Scaling ANSYS Fluent: From Workstations to Supercomputers

The performance and scalability of Ansys Fluent simulations exhibit a significant and often dramatic transformation as one moves from standalone engineering workstations to small departmental clusters, and eventually to large-scale High-Performance Computing (HPC) systems or even national-level supercomputers. Understanding this scaling behavior – how the software’s performance changes with increasing computational resources – is crucial for users to select the most appropriate computational platform for their specific Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) needs. This involves balancing factors like the initial cost of hardware or cloud resources, the desired turnaround time for simulations, the complexity and size of the problems being solved, and the overall efficiency of resource utilization. While a powerful modern workstation can certainly handle smaller or moderately sized Fluent jobs, it quickly encounters fundamental limitations in core count, memory capacity, memory bandwidth, and I/O performance when faced with the demands of industrial-scale or research-intensive problems. This is precisely where the true power and necessity of parallel computing in HPC become unmistakably evident.

On a typical high-end engineering workstation (e.g., equipped with one or two multi-core CPUs providing 8 to perhaps 64 cores in total, and 64GB to 256GB or even 512GB of RAM), Ansys Fluent can provide reasonable interactive performance for pre-processing, post-processing, and solving simulations with mesh sizes up to a few million cells, or perhaps low tens of millions if the physics models are relatively simple and the geometry is not overly complex. For such cases, solution times might range from hours to a day. However, for larger meshes (e.g., 30-50 million cells or more), more complex physics (like transient simulations involving LES, detailed combustion models, or multiphase flows), or when many design iterations are needed quickly, workstations become severely bottlenecked. Solution times can stretch into many days or even weeks, rendering them impractical for typical project timelines. Furthermore, if the memory required by the simulation exceeds the workstation’s available RAM, the operating system will resort to using disk-based virtual memory (swapping), which is orders of magnitude slower than physical RAM and effectively grinds the simulation performance to a virtual halt. The limited number of cores also restricts the achievable parallelism, capping the potential speedup regardless of how well the software itself is parallelized.

Transitioning to a small or medium-sized HPC cluster (e.g., consisting of 4-16 nodes, where each node might be a dual-socket HPC server with 32-128 cores, interconnected by a high-speed fabric like InfiniBand or fast Ethernet with RDMA) offers a substantial leap in capability. Such systems, often found in departmental settings or within medium-sized enterprises, can comfortably handle Ansys Fluent simulations with mesh sizes ranging from tens of millions to potentially over a hundred million cells, depending on the specifics. The distributed memory architecture allows much larger problems to be tackled than on any single workstation, as the total memory is the aggregate of all nodes. The significantly increased total core count, enabled by cluster computing, drastically reduces solution times, often bringing multi-day workstation runs down to a few hours or an overnight job. For many common industrial CFD problems, a well-configured small to medium HPC cluster provides an excellent balance of performance, cost, and manageability. However, as the core count used for a single job increases, the efficiency of the network interconnect (both its latency and bandwidth) and the parallel efficiency of the Fluent solver for that specific problem become increasingly critical to maintaining good scaling and avoiding diminishing returns.

For truly grand-challenge problems—simulations involving hundreds of millions or even billions of cells, extremely complex multi-physics interactions (like tightly coupled fluid-structure-thermal simulations), or very long-duration transient events requiring millions of time steps—large HPC clusters and national or international supercomputers are required. These systems may feature hundreds or thousands of interconnected nodes, leading to total core counts in the tens or hundreds of thousands (or even millions), and petabytes of both RAM and parallel storage. On such platforms, Ansys Fluent can be used to solve problems that are simply intractable on smaller systems, pushing the frontiers of scientific and engineering knowledge. However, achieving efficient scaling on these massive systems is a highly complex task. Amdahl’s Law, which highlights the limiting effect of serial code sections, becomes increasingly pertinent. Communication overhead across such a vast number of nodes, even with state-of-the-art interconnects, can also become a significant fraction of the total runtime. Therefore, both strong scaling (solving a fixed-size problem faster with more cores) and weak scaling (solving a proportionally larger problem in roughly the same amount of time with more cores) studies are essential to characterize performance and optimize resource usage. Ansys Fluent developers continually work to improve the software’s scalability on these extreme-scale systems through algorithmic enhancements and optimized MPI communication patterns. MR CFD helps clients navigate these complex scaling considerations, ensuring that whether they are using a modest in-house HPC cluster or require access to larger national facilities for their most demanding hpc for ansys fluent needs, the computational resources are utilized as effectively and economically as possible.

A conceptual representation of Ansys Fluent speedup might look like this:

(Imagine a graph with “Number of Cores” on the X-axis and “Speedup” on the Y-axis. An “Ideal Linear Speedup” line goes up diagonally (e.g., at 45 degrees if axes are scaled appropriately). An “Actual Fluent Speedup” curve starts close to the ideal line for small core counts, then gradually deviates and flattens out at higher core counts due to parallel overheads (communication, synchronization, load imbalance, serial fractions). The curve should still show significant gains over workstation-level core counts, but the efficiency (Actual Speedup / Number of Cores) decreases as N increases.)

This impressive scaling behavior across diverse hardware platforms is enabled by specific and sophisticated parallel processing techniques embedded within CFD solvers like Ansys Fluent. Let’s delve into some of the key parallel approaches commonly employed in these demanding simulations.

Parallel Processing Techniques in CFD Simulations

The remarkable ability of Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) software like Ansys Fluent to effectively scale across a wide range of High-Performance Computing (HPC) systems, from small clusters to massive supercomputers, is not accidental. It is the direct result of sophisticated and carefully engineered parallel processing techniques embedded within the core of the solvers and supporting infrastructure. These techniques are specifically designed to efficiently distribute the immense computational workload and vast amounts of data associated with complex fluid flow simulations across multiple processors or compute nodes in an HPC server environment. The most fundamental of these techniques is domain decomposition, which is complemented by parallelized numerical algorithms, strategies for maintaining data consistency across distributed data, and mechanisms for achieving good load balance among the processing elements.

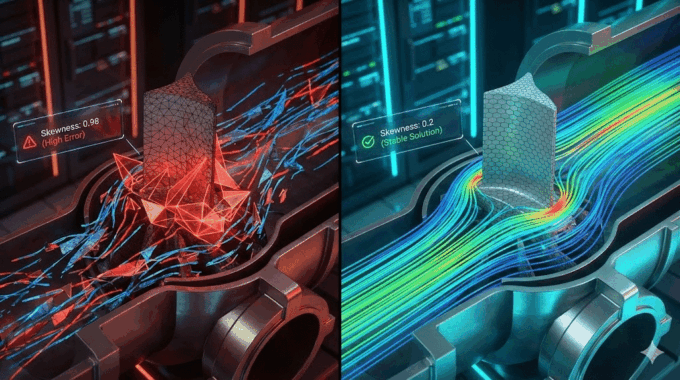

Domain Decomposition is the cornerstone of parallelism in most modern CFD codes, including Ansys Fluent. The physical geometry or computational domain, which is represented by a mesh composed of millions or billions of individual cells or elements, is algorithmically divided into multiple smaller sub-domains or partitions. Each of these partitions is then assigned to a separate parallel process (typically an MPI process, in the context of distributed memory systems), which, in turn, runs on a specific CPU core or is managed by a group of cores. Each process becomes responsible for performing the primary computational tasks – solving the discretized Navier-Stokes equations and other relevant transport equations – only for the cells that lie within its assigned sub-domain. This intelligent distribution of cells effectively parallelizes both the computational work (as each process handles a smaller piece of the overall problem) and the memory requirement (as each process only needs to store the geometric and solution data for its local portion of the mesh, plus some overhead for communication buffers). Common algorithms used for partitioning large, often unstructured, meshes include recursive coordinate bisection, inertial bisection, and more advanced graph partitioning methods like METIS or ParMETIS. These graph-based methods treat the mesh as a graph (cells are vertices, cell-to-cell adjacencies are edges) and aim to create partitions that minimize the number of “cut edges” (connections between cells in different partitions, which represent communication requirements) while keeping the number of cells (or a measure of computational work) per partition roughly equal to ensure good load balancing.

To ensure a correct and globally consistent solution, processes must communicate information across the artificial boundaries of their sub-domains. Cells located at the interface between two (or more) partitions require data values (e.g., pressure, velocity, temperature) from their neighboring cells which reside in an adjacent partition and are managed by a different process. To facilitate this, these interface cells are often conceptually extended with one or more layers of “halo” or “ghost” cells – these are essentially copies of cells from neighboring partitions that store the necessary data from those neighbors. Before each iteration (or sometimes sub-iteration) of the main solver loop, processes engage in a communication phase where they exchange data for these halo cells. This typically involves MPI send and receive operations (or more optimized collective operations if applicable) over the network interconnect. The efficiency, latency, and bandwidth of this communication step are absolutely critical for overall parallel performance, especially as the number of partitions (and thus the surface-to-volume ratio of the sub-domains) increases. Beyond geometric decomposition, Ansys Fluent also employs highly parallelized numerical algorithms for all key stages of the solution process. Iterative linear system solvers (such as Conjugate Gradient methods, GMRES, BiCGSTAB) and powerful preconditioners (like Algebraic Multigrid – AMG, or Incomplete LU factorization) that are used to solve the large, sparse systems of algebraic equations arising from the discretization of the governing PDEs are themselves meticulously parallelized to operate efficiently on distributed data. For instance, AMG methods involve constructing and solving problems on a hierarchy of successively coarser grids; each step of this process, including inter-grid transfer operators like restriction and prolongation, as well as smoothing operations on each grid level, is carefully adapted for parallel execution across many cores.

Load balancing is another crucial aspect for sustained parallel efficiency. If some processes are assigned significantly more computational work than others (e.g., due to having more cells, more complex cell types, or regions requiring more solver iterations locally), the lightly loaded processes will finish their portion of the work early and then sit idle, waiting for the heavily loaded processes to catch up. This leads to poor overall resource utilization and extends the total execution time of the simulation. Ansys Fluent incorporates sophisticated algorithms to distribute the computational workload as evenly as possible during the initial domain decomposition phase. It may also offer options for dynamic load balancing in certain scenarios (e.g., for simulations with adaptive mesh refinement or highly non-uniform physics), where the workload distribution can change during the simulation, although dynamic re-balancing can introduce its own communication and data migration overheads. MR CFD’s expertise in hpc for ansys fluent includes a deep understanding of these parallel settings and techniques. We guide clients in choosing appropriate decomposition strategies, tuning solver parameters for parallel execution, and configuring MPI environments to ensure that their simulations run efficiently and scale well on state-of-the-art cluster computing infrastructure, maximizing throughput and minimizing time-to-solution.

(A simple diagram could show a 2D mesh, perhaps of an airfoil, divided into, say, 8 or 16 colored sub-domains. Arrows between adjacent sub-domains of different colors could indicate the data exchange required for halo cells. The caption could read: “Domain Decomposition in a CFD Mesh: The computational domain is partitioned into sub-domains, each handled by a parallel process. Halo cells (not explicitly shown) facilitate data exchange at partition boundaries.”)

While these sophisticated techniques enable incredible speedups and the solution of previously intractable problems, parallel computing is not without its inherent difficulties and performance pitfalls. We will now address some of the common challenges encountered in harnessing the power of HPC.

Overcoming Parallel Computing Challenges in HPC

While parallel computing in HPC offers transformative capabilities for tackling complex problems, achieving efficient and scalable performance is often fraught with inherent challenges. These hurdles can significantly limit the actual speedup obtained from adding more processors and require careful consideration in both application software design and HPC system configuration and tuning. Understanding these common bottlenecks—such as inter-process communication overhead, critical synchronization issues, workload imbalance among parallel tasks, and the persistent impact of unavoidable serial code sections—is crucial for anyone working with High-Performance Computing (HPC) systems. This is particularly true for users of demanding, data-intensive applications like Ansys Fluent running on an HPC server or large cluster computing environment. Successfully overcoming or meticulously mitigating these challenges is key to unlocking the full performance potential of parallel architectures and ensuring that computational resources are used effectively.

Communication Overhead is one of the most significant and pervasive limiting factors in distributed-memory parallel computing, which is the dominant model for large-scale HPC. Processes running on different nodes in a cluster computing environment need to exchange data to coordinate their work and maintain a consistent view of the overall problem state. In CFD simulations, this typically involves exchanging “halo” or “ghost” cell data between adjacent mesh partitions, or performing global reductions to calculate convergence criteria. This communication takes time, which is determined by several factors: the latency of the network interconnect (the fixed time delay to initiate a message transfer), the bandwidth of the interconnect (the rate at which data can be transferred once the transfer starts), the frequency of communication events, and the volume of data being exchanged in each event. As the number of processes (and thus, often, the number of sub-domain boundaries) increases, the proportion of time spent on communication relative to useful computation can also increase, eventually diminishing the returns from adding more cores. Collective communication operations (e.g., MPI_Allreduce, MPI_Bcast, MPI_Alltoall), where all processes in a communicator participate, can be particularly costly on large numbers of processors if not implemented efficiently by the MPI library and supported by a high-performance, contention-free network topology. Minimizing both the frequency and volume of communication, and overlapping communication with computation where possible, are key optimization strategies.

Synchronization points in a parallel program, where processes must wait for one another to reach a common state before proceeding, can also introduce significant overhead and idle time. For example, if different parts of a complex calculation must complete before the next major step can begin (e.g., all sub-domains must finish their local solver iterations before global convergence checks can be performed), all processes might wait at a barrier. If some processes arrive at the synchronization point much earlier than others (often a consequence of load imbalance or variations in computational paths), they remain idle, wasting valuable computational resources until the slowest process catches up. Frequent or poorly managed synchronization can severely degrade parallel efficiency. Load Imbalance itself is a major challenge that directly contributes to synchronization overhead. If the computational workload is not evenly distributed among the parallel processes, some will finish their assigned tasks quickly while others lag behind, leading to poor overall resource utilization and extending the total execution time to that of the slowest process. In CFD, load imbalance can occur due to uneven mesh partitioning (some partitions having more cells or more complex cell types), or because the physics being solved (e.g., regions with chemical reactions or phase change) leads to significantly more computational effort in certain parts of the domain than others. Dynamic load balancing techniques can help but often come with their own overhead of data migration and re-partitioning.