HPC vs. Regular Computing: The Crucial Differences Everyone Misses

In today’s data-driven world, the demand for computational power is exploding. From groundbreaking scientific research to complex engineering simulations and the intricate algorithms powering artificial intelligence, the limits of regular computing are constantly being tested. While desktop computers and standard servers are adept at handling everyday tasks, they falter when faced with problems of immense scale and complexity. This is where High-Performance Computing (HPC) steps in, offering a paradigm shift in processing capability. Understanding the fundamental distinctions between HPC and regular computing is no longer a niche concern; it’s crucial for anyone involved in advanced computational endeavors. These differences are not merely about speed; they encompass architecture, parallelism, data handling, and the very philosophy of problem-solving. Failing to grasp these nuances can lead to significant underestimation of computational needs, inefficient workflows, and ultimately, missed opportunities for innovation.

This comprehensive guide, drawing on MR CFD’s extensive expertise in computational engineering, will delve into the critical differences between HPC and regular computing. We will explore the architectural underpinnings, the power of parallel computing, and how these systems handle challenges that would overwhelm their conventional counterparts. Specifically, we will examine the demanding world of Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) and how software like Ansys Fluent leverages HPC to unlock unprecedented simulation potential. By the end of this exploration, you’ll have a clear understanding of why HPC is not just an incremental upgrade, but a transformative technology essential for tackling the most complex computational problems of our time. We will also explore how MR CFD can be your trusted advisor in navigating the complexities of HPC for your specific engineering challenges, ensuring you harness the full power of these advanced systems.

Ready to Make the Leap from Regular Computing to HPC Power for ANSYS?

You’ve seen the fundamental difference: while regular computing handles everyday tasks, High-Performance Computing is the essential engine for tackling the complex, large-scale problems inherent in advanced ANSYS simulations. If your current workstation or standard server is a bottleneck, preventing you from achieving faster results or exploring larger models, it’s time to step into the realm of true HPC. Our ANSYS HPC service offers seamless, on-demand access to the high-performance computing resources you need, fully optimized for ANSYS software like Fluent.

Stop being limited by conventional hardware. Experience the dramatic acceleration that only HPC can provide, completing your complex ANSYS solves in hours, not days. This transition accelerates your design and analysis cycles, enables you to work with larger and more detailed models than ever before, and significantly boosts overall productivity. Leverage the power you now understand is necessary for your demanding ANSYS work, without the complexity and cost of building your own HPC infrastructure.

Explore HPC for Faster ANSYS CFD Solves

Introduction to HPC vs. Regular Computing

The computational landscape is bifurcated, broadly speaking, into two domains: regular computing and High-Performance Computing (HPC). Regular computing encompasses the desktops, laptops, and standard servers that facilitate our daily digital lives and business operations. These systems are designed for a wide array of general-purpose tasks, from word processing and web Browse to managing databases and running enterprise applications. Their design prioritizes versatility, cost-effectiveness for individual users or small-scale applications, and ease of use. While powerful in their own right, they are fundamentally architected for serial processing or limited parallelism, handling tasks sequentially or a few at a time. This inherent limitation becomes a critical bottleneck when faced with problems requiring the simultaneous analysis of vast datasets or the execution of billions of calculations to model complex phenomena.

High-Performance Computing (HPC), in stark contrast, is engineered to tackle computational problems that are far beyond the scope of regular computing. These are typically challenges characterized by their immense scale, complexity, and the need for rapid turnaround times. Think of weather forecasting, genomic sequencing, intricate financial modeling, drug discovery, and, critically for our focus, advanced engineering simulations like Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD). HPC systems achieve their extraordinary capabilities through massively parallel computing architectures, specialized hardware components, and sophisticated software environments. They are not just “faster” computers; they represent a fundamentally different approach to computation, designed to solve problems that would otherwise be intractable. The significance of understanding these differences lies in recognizing when the computational demands of a task necessitate a leap from the familiar realm of regular computing to the specialized power of HPC. This recognition is pivotal for innovation, efficiency, and maintaining a competitive edge in research and industry. As we delve deeper, we will unpack these distinctions, providing clarity on what truly sets HPC apart and why it’s indispensable for modern computational science and engineering.

This initial distinction sets the stage for a more granular exploration. Next, we will precisely define what constitutes High-Performance Computing and traditional (or regular) computing, establishing a solid technical foundation for the detailed comparisons that will follow.

HPC vs. Traditional Computing

To truly appreciate the chasm between High-Performance Computing (HPC) and traditional computing (often referred to as regular computing), it’s essential to establish clear definitions. Traditional computing systems are the workhorses of our daily digital interactions. They are typically built around a single multi-core processor (CPU), a moderate amount of Random Access Memory (RAM), and local storage like Hard Disk Drives (HDDs) or Solid-State Drives (SSDs). The operating systems (e.g., Windows, macOS, standard Linux distributions) and software applications are optimized for responsiveness in interactive use and handling a diverse range of tasks, but generally not for sustained, massively parallel workloads. For instance, a typical office desktop might have a CPU with 4 to 8 cores, 8GB to 32GB of RAM, and a single GPU primarily for display purposes. These systems excel at tasks like document editing, web Browse, modest data analysis in spreadsheets, or running business software. Their architecture is primarily geared towards minimizing latency for a single user’s active tasks rather than maximizing aggregate throughput for large-scale computations.

High-Performance Computing (HPC), on the other hand, refers to the practice of aggregating computing power in a way that delivers much higher performance than one could get out of a typical desktop computer or workstation. 1 An HPC system, often a cluster computing environment, is a carefully orchestrated ensemble of many interconnected computers (nodes), each of which can be a powerful multi-core server in its own right. These nodes work in concert to solve a single, large problem. Key characteristics of HPC include:

Massive Parallelism: Utilizing hundreds or even thousands of processor cores simultaneously. This involves not just multi-core CPUs but increasingly, GPU acceleration to handle specific types of computations with extreme efficiency.

- High-Bandwidth, Low-Latency Interconnects: Specialized networking fabrics (e.g., InfiniBand, Omni-Path) are used to ensure rapid communication between nodes, which is crucial for parallel algorithms where intermediate results must be shared frequently.

- Large and Fast Storage Systems: HPC systems often connect to parallel file systems (e.g., Lustre, GPFS) capable of handling terabytes or petabytes of data with very high read/write speeds.

- Specialized Software Stack: This includes operating systems optimized for cluster computing, parallel programming libraries (like MPI and OpenMP), job schedulers (e.g., Slurm, PBS), and performance analysis tools.

For example, a modern HPC cluster might consist of hundreds of nodes, each with two 32-core CPUs, 256GB of RAM, and multiple GPUs, all connected by an InfiniBand network. Such a system can sustain teraflops (trillions of floating-point operations per second) or even petaflops (quadrillions of FLOPS). This stark contrast in scale and architecture with regular computing underpins the ability of HPC to tackle problems like simulating the airflow over an entire aircraft wing or modeling global climate change – tasks that are simply infeasible on traditional systems. MR CFD leverages these very capabilities to provide cutting-edge Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) solutions, demonstrating daily how HPC transcends the limitations of regular computing.

Having established these foundational definitions, we can now proceed to dissect the fundamental architectural differences that give HPC systems their distinct operational advantages over their traditional counterparts.

How HPC Systems Fundamentally Differ

The profound performance gap between High-Performance Computing (HPC) systems and regular computing environments stems from deep-seated architectural divergences. These aren’t just incremental improvements; they represent a specialized design philosophy focused on maximizing parallel throughput and computational density. One of the most visible differences lies in the processors. While a high-end desktop might boast a CPU with 8, 16, or even 32 cores, HPC nodes typically feature server-grade CPUs with higher core counts, larger caches, and more memory channels. Furthermore, HPC systems extensively utilize co-processors, particularly GPU acceleration. GPUs, originally designed for graphics rendering, possess thousands of smaller cores, making them exceptionally efficient at performing the same operation on large datasets simultaneously (SIMD/SIMT parallelism). This makes them ideal for the matrix and vector operations prevalent in scientific and engineering computations, including Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD). The integration of CPUs and GPUs in a heterogeneous architecture is a hallmark of modern HPC design.

Beyond the processing units, the memory hierarchy in HPC systems is far more sophisticated and performance-critical than in regular computing. HPC applications often deal with massive datasets that must be accessed quickly by numerous cores. Therefore, HPC nodes are equipped with significantly larger amounts of RAM, often with higher bandwidth and error-correcting code (ECC) capabilities. The memory subsystem is carefully balanced with the processor capabilities to prevent cores from starving for data. This includes deeper cache hierarchies (L1, L2, L3) and careful consideration of Non-Uniform Memory Access (NUMA) architectures within nodes to optimize data locality. In contrast, regular computing systems, while benefiting from faster RAM, do not typically face the same relentless demand from thousands of cores working on a tightly coupled problem, making their memory systems less complex and less of a bottleneck for their intended tasks.

The third pillar of architectural differentiation is the interconnect. In a standalone desktop, component communication largely occurs over the motherboard’s buses. In an HPC cluster, which is a collection of interconnected nodes, the network interconnect is paramount. Standard Ethernet, while adequate for office networks or small server clusters, becomes a major bottleneck in large-scale HPC due to its higher latency and lower bandwidth. HPC systems employ specialized, high-speed interconnects like InfiniBand or proprietary technologies (e.g., Cray’s Slingshot). These interconnects provide extremely low latency (microseconds or less) and very high bandwidth (hundreds of Gigabits per second), which are essential for the frequent communication and synchronization required by parallel algorithms running across many nodes. This allows the cluster to behave more like a single, massive computational resource rather than a collection of disparate computers. The performance of these network interconnects is often a hidden but crucial multiplier for overall application performance, especially in fields like CFD where extensive data exchange between processing elements is common. MR CFD understands that optimizing for these architectural nuances is key to achieving peak performance in complex simulations.

These architectural distinctions—processors, memory, and interconnects—are fundamental to the capabilities of HPC. Next, we will explore how these architectures specifically enable the core advantage of HPC: massively parallel processing.

Parallel Processing: The Core Advantage of HPC Systems

The defining characteristic and primary advantage of High-Performance Computing (HPC) systems is their inherent ability to perform parallel processing on a massive scale. Unlike regular computing, which predominantly relies on serial processing (executing instructions one after another, or with limited parallelism on a few CPU cores), HPC architectures are explicitly designed to divide large, complex problems into smaller, independent tasks that can be solved concurrently by a multitude of processors or cores. This simultaneous computation is the engine that drives the extraordinary performance of HPC systems, enabling them to tackle problems that would take years, decades, or even centuries on a traditional computer. The philosophy behind parallel computing is “many hands make light work,” applied to computational tasks. Whether it’s through shared-memory parallelism within a single node (using threads via OpenMP, for example) or distributed-memory parallelism across multiple nodes in a cluster computing environment (using message passing via MPI), the goal is the same: keep as many processing units as busy as possible, working collaboratively on different parts of the same overarching problem.

The implementation of parallel processing in HPC involves sophisticated parallel algorithms that are designed to efficiently partition the data and distribute the computational load. For instance, in a Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) simulation using Ansys Fluent, a complex geometry (like an aircraft wing or a chemical reactor) is divided into millions or even billions of small cells, forming a mesh. The governing equations of fluid flow (Navier-Stokes equations) are then solved for each of these cells. An HPC system can distribute these cells among its numerous cores, with each core responsible for the calculations within its assigned subset of cells. These cores then communicate with each other to exchange boundary information and synchronize their calculations. The efficiency of this process depends heavily on the HPC architecture, including the speed of the network interconnects and the structure of the memory hierarchy, as well as the design of the parallel algorithm itself. GPU acceleration further enhances this by offloading computationally intensive portions of the code to the thousands of cores on a GPU, dramatically speeding up calculations for suitable workloads.

Real-world implications of this massive parallelism are transformative. In scientific research, it allows for more accurate simulations of complex physical phenomena, such as protein folding for drug discovery or the evolution of galaxies. In engineering, HPC enables the design and testing of virtual prototypes with remarkable fidelity, reducing the need for expensive and time-consuming physical experiments. For example, automotive manufacturers use HPC for crash simulations and aerodynamic analysis, leading to safer and more fuel-efficient vehicles. Weather forecasting agencies rely on HPC to run complex atmospheric models, providing more accurate and timely predictions that can save lives and property. MR CFD’s expertise in leveraging parallel processing for Ansys Fluent simulations means clients can achieve higher fidelity results faster, optimizing designs and accelerating innovation cycles. Without the parallel processing capabilities of HPC, these advancements would simply not be possible at the scale and speed required today.

Having understood the power of parallelism, it’s crucial to consider how this capability allows HPC systems to manage computational tasks and data volumes that far exceed the limits of regular computing. We will now examine the aspects of scale and capacity.

Scale and Capacity: Breaking Through Regular Computing Limitations

The sheer scale and capacity of High-Performance Computing (HPC) systems represent a fundamental breakthrough compared to the inherent limitations of regular computing. Traditional computers, even high-end workstations, are constrained by their single-system architecture. They have a finite amount of memory, a limited number of processing cores, and storage that, while potentially large, is accessed through a relatively narrow bandwidth. When confronted with problems that involve massive datasets or require an astronomical number of calculations, these systems quickly hit a wall. For instance, a complex Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) simulation might involve a mesh with tens or hundreds of millions of cells, requiring terabytes of RAM to store the model and its intermediate solution data. A regular computing system simply lacks the memory capacity to hold such a problem, let alone process it efficiently. Similarly, simulating a physical process over a meaningful timescale might require quintillions (1018) of floating-point operations, a task that would take a single desktop CPU an impractical amount of time.

HPC systems are specifically designed to overcome these limitations of scale. Cluster computing architectures, by their very nature, allow for the aggregation of resources. Memory capacity is pooled across hundreds or thousands of nodes, providing the terabytes or even petabytes of distributed memory needed for grand-challenge problems. For example, if a simulation requires 2TB of RAM, and each HPC node has 256GB, the problem can be distributed across 8 nodes (simplistically speaking, in reality, it’s more complex due to data partitioning and communication overhead). This distributed memory architecture, managed by protocols like the Message Passing Interface (MPI), allows each processing core to work on its portion of the data while having access, via the high-speed network interconnects, to data held by other nodes when necessary. This scalability in memory is mirrored in processing power; adding more nodes increases the total number of available cores, allowing for more parallel processing and thus faster solution times for suitably parallelizable problems.

The impact of this enhanced scale and capacity is profound across numerous fields. In genomics, HPC enables the analysis of entire population datasets to identify genetic markers for diseases. In astrophysics, it allows for the simulation of cosmic evolution involving billions of particles. For engineering firms like MR CFD, leveraging HPC for Ansys Fluent simulations means that clients are no longer constrained by the size or complexity of the geometries they can analyze. Extremely detailed meshes, leading to more accurate predictions of fluid behavior, become feasible. Multi-scale models, capturing phenomena from the micro-level to the macro-level, can be tackled. The ability to handle such scale not only provides more accurate results but also opens up new avenues of investigation that were previously computationally prohibitive. Consider the oil and gas industry, where HPC is used for reservoir simulation, processing vast amounts of seismic data to optimize extraction strategies – a task far beyond any regular computing setup. The capacity of HPC to store and process these enormous datasets is as critical as its raw computational speed.

This discussion of scale naturally leads to a more detailed examination of one of the critical components enabling this capacity: the specialized memory architectures within HPC systems. We will now delve into why the memory hierarchy is so much more critical and complex in HPC.

The Memory Hierarchy: Why It Matters More in HPC

While all computing systems utilize a memory hierarchy – ranging from fast but small CPU registers and caches to slower but larger main memory (RAM) and then to even slower disk storage – its design and performance are exceptionally critical in High-Performance Computing (HPC). In regular computing, the memory system is designed to support a relatively small number of cores and a diverse range of applications where data access patterns can be quite varied. While important, minor inefficiencies in memory access might lead to noticeable slowdowns for a user but are rarely catastrophic system-wide bottlenecks for typical desktop tasks. The primary concern is often providing enough RAM to keep frequently used applications and their data in memory, reducing reliance on much slower disk-based virtual memory.

In stark contrast, the memory hierarchy in an HPC system is a meticulously engineered component that can make or break the performance of massively parallel computing applications. HPC applications, such as large-scale Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) simulations, often exhibit intense memory access patterns. Thousands of cores simultaneously demand data, and if the memory subsystem cannot keep pace, these expensive cores will sit idle, wasting computational cycles – a phenomenon known as memory starvation. Therefore, HPC nodes are typically equipped with significantly more RAM per core than regular computing systems, and this RAM is often faster and features more channels to the CPU(s) to increase overall memory bandwidth. For instance, a server CPU in an HPC node might support 8 or 12 memory channels, compared to 2 or 4 in a desktop CPU, directly translating to higher data throughput. Furthermore, Error-Correcting Code (ECC) memory is standard in HPC to ensure data integrity, as even a single bit-flip in a long-running simulation involving petabytes of data movement can corrupt results.

Beyond raw capacity and bandwidth, the organization of memory within a node (NUMA – Non-Uniform Memory Access) and across the cluster computing environment is paramount. In NUMA architectures, each CPU (or socket) has its own local memory. Accessing this local memory is faster than accessing memory attached to another CPU on the same node. HPC programmers and sophisticated software, like Ansys Fluent, must be NUMA-aware to ensure that data is kept as close as possible to the cores processing it. This minimizes latency and maximizes bandwidth utilization. On a broader cluster scale, the “memory” extends to the distributed memory across all nodes, accessed via network interconnects. The effective management of data movement between on-node caches, main memory, and the memory of other nodes is crucial for achieving scalability. Specialized parallel file systems also form an extension of this hierarchy, designed to feed data to the cluster at extremely high rates. MR CFD’s expertise includes optimizing simulations to leverage these complex memory hierarchies effectively, ensuring that memory bottlenecks do not throttle the immense processing power of HPC clusters. The subtle interplay between cache coherence protocols, memory controller performance, and data placement strategies is far more pronounced and impactful in HPC than any casual user of regular computing might ever encounter.

The efficiency of data movement within and between nodes, heavily reliant on the memory hierarchy, is complemented by another critical component: the network interconnects. Next, we will explore how these high-speed communication fabrics act as a hidden performance multiplier in HPC environments.

Network Interconnects: The Hidden Performance Multiplier

While processing power (CPUs and GPUs) and memory capacity are often the headline features of High-Performance Computing (HPC) systems, the network interconnects that link the individual nodes within a cluster computing environment are a critical, albeit sometimes overlooked, performance multiplier. In regular computing, networking typically involves standard Ethernet connections (Gigabit or perhaps 10-Gigabit Ethernet) primarily used for internet access, file sharing, or connecting to peripherals. The demands on this network are generally bursty and latency tolerance is relatively high. If an email takes an extra half-second to send or a webpage loads a fraction slower, it’s often imperceptible or a minor inconvenience. This is a stark contrast to the demands placed on network interconnects in an HPC cluster, where hundreds or thousands of nodes must communicate intensively and synchronize frequently to solve a single, tightly coupled problem.

HPC interconnects are specialized, high-bandwidth, low-latency fabrics designed for the demanding communication patterns of parallel algorithms. Technologies like InfiniBand, Omni-Path (though its development has largely ceased, many systems still use it), and proprietary solutions like Cray’s Slingshot or HPE’s Slingshot (derived from Cray’s technology) offer significantly superior performance characteristics compared to standard Ethernet.

- Low Latency: This refers to the time it takes for a small message to travel from one node to another. In HPC, latencies are measured in microseconds (millionths of a second) or even nanoseconds, whereas Ethernet latencies are typically in milliseconds (thousandths of a second). Low latency is crucial for applications that require frequent, small messages for synchronization or data exchange, common in Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) solvers.

- High Bandwidth: This is the rate at which data can be transferred between nodes, typically measured in Gigabits per second (Gbps) or Gigabytes per second (GB/s). Modern HPC interconnects offer per-link bandwidths of 100 Gbps, 200 Gbps, or even higher, far exceeding standard Ethernet. This is vital for applications that need to move large blocks of data, such as when redistributing domains in a simulation or writing large checkpoint files.

- Topology and Scalability: HPC interconnects are often arranged in sophisticated topologies (e.g., fat-tree, dragonfly, torus) designed to provide high bisection bandwidth (a measure of the network’s capacity to handle global communication) and to scale efficiently to thousands of nodes while minimizing contention and maximizing path diversity.

The performance of these network interconnects directly impacts the scalability of parallel applications. If the interconnect becomes a bottleneck, adding more processing nodes may yield diminishing returns or even degrade performance, as cores spend more time waiting for data than computing. In Ansys Fluent simulations, for instance, when a fluid domain is decomposed and distributed across multiple nodes, the boundaries of these subdomains must be communicated between neighboring nodes at each iteration of the solver. The speed and efficiency of this data exchange are entirely dependent on the interconnect. MR CFD recognizes that a well-designed and robust interconnect is as important as the processors and memory for achieving optimal simulation throughput. The “hidden” aspect of this performance multiplier is that users don’t often interact directly with the interconnect, but its characteristics profoundly influence the wall-clock time of their simulations, making it a cornerstone of effective HPC architecture.

Having established the architectural superiority of HPC, particularly its parallel computing prowess, sophisticated memory hierarchy, and high-performance network interconnects, we can now focus on how these capabilities specifically benefit a highly demanding application area: Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD), with a particular emphasis on Ansys Fluent.

Computational Fluid Dynamics: Why Ansys Fluent Demands HPC

Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) is a branch of fluid mechanics that uses numerical analysis and data structures to analyze and solve problems that involve fluid flows. It’s a cornerstone of modern engineering design and analysis, allowing for the simulation of phenomena like airflow over an aircraft wing, coolant flow through an engine, blood flow in arteries, pollutant dispersion in the atmosphere, or the mixing of reactants in a chemical process. Software like Ansys Fluent is a leading commercial CFD package that provides a comprehensive suite of tools for modeling these complex fluid dynamics. However, the very nature of CFD simulations makes them exceptionally computationally intensive, often pushing the boundaries of what is possible with regular computing and creating a strong demand for High-Performance Computing (HPC) resources.

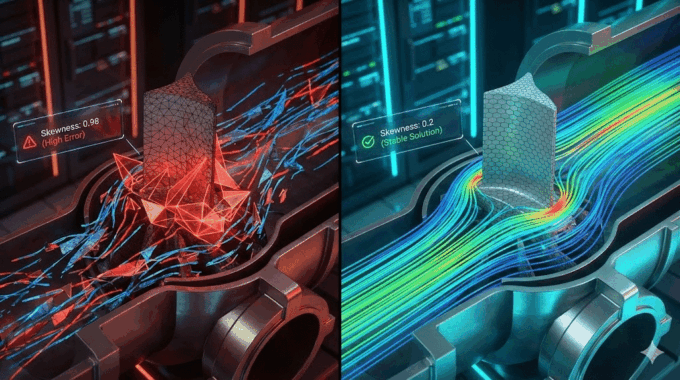

The primary reason for this demand lies in the fundamental mathematical models underpinning CFD: the Navier-Stokes equations. These are a set of coupled, non-linear partial differential equations that describe the motion of viscous fluid substances. There is no general analytical solution to these equations for most real-world scenarios. Therefore, CFD software like Ansys Fluent employs discretization methods (e.g., Finite Volume Method, Finite Element Method) to transform these continuous equations into a system of algebraic equations that can be solved numerically. This involves dividing the geometric domain of interest into a large number of small cells or elements, forming a computational mesh. The accuracy of a CFD simulation is often directly related to the fineness of this mesh size; more cells generally lead to more accurate results but also drastically increase the computational cost. A typical industrial CFD simulation can easily involve millions, tens of millions, or even billions of mesh cells. Solving the algebraic equations for each of these cells, iteratively, and for multiple physical variables (pressure, velocity components, temperature, species concentration, turbulence quantities, etc.) requires an enormous number of calculations.

Furthermore, many CFD problems are inherently unsteady (transient), meaning the flow field changes over time. Simulating these transient phenomena requires solving the equations at many small time steps, adding another dimension of computational expense. Advanced CFD models also incorporate complex physics, such as turbulence models (e.g., RANS, LES, DES), multiphase flows, heat transfer, chemical reactions, and fluid-structure interaction. Each additional physical model adds more equations and more complexity to the system, further escalating the computational requirements. For example, a Large Eddy Simulation (LES) for turbulence, which offers higher fidelity than RANS models, demands significantly finer meshes and smaller time steps, pushing computational costs up by orders of magnitude. It quickly becomes apparent that even moderately complex CFD simulations in Ansys Fluent can easily overwhelm the capabilities of regular computing systems, leading to impractically long run times or forcing engineers to oversimplify models, thereby compromising accuracy. This is precisely where HPC becomes indispensable, offering the parallel computing power, memory capacity, and I/O performance needed to tackle these demanding simulations effectively and within reasonable timeframes, a capability central to MR CFD’s service offerings.

Understanding this inherent demand sets the stage for a direct comparison. We will now look at the specific limitations and bottlenecks encountered when attempting to run complex Ansys Fluent simulations on regular computing systems.

Ansys Fluent on Regular Computing: The Limitations and Bottlenecks

Attempting to run complex Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) simulations using sophisticated software like Ansys Fluent on regular computing hardware quickly exposes a series of critical limitations and performance bottlenecks. While regular computing systems, such as high-end desktop workstations, can handle very simple CFD problems or preliminary model setups, they are fundamentally ill-equipped for the demands of industrial-scale or research-grade simulations. The primary bottleneck is often the limited number of CPU cores. Ansys Fluent is designed to leverage parallel processing, but a typical desktop with 4, 8, or even 16 cores can only provide a fraction of the parallelism available in an HPC cluster with hundreds or thousands of cores. This directly translates to excruciatingly long simulation run times. A simulation that might complete in a few hours on an HPC system could take days, weeks, or even become practically infeasible on a desktop, significantly delaying project timelines and hindering iterative design processes.

Memory capacity is another major constraint. As discussed, realistic CFD models often require large mesh sizes to accurately capture complex geometries and flow features. Each cell in the mesh stores multiple variables (pressure, velocity components, temperature, turbulence parameters, etc.), and the solver requires additional memory for gradients, fluxes, and other intermediate calculations. A simulation with 20 million cells could easily require 60-100GB of RAM, and more complex physics or finer meshes will demand even more. Most regular computing systems top out at 32GB, 64GB, or perhaps 128GB of RAM in high-end workstations. Exceeding this available RAM forces the system to use disk-based virtual memory, which is orders of magnitude slower than physical RAM. This “swapping” leads to a dramatic slowdown, effectively grinding the simulation to a halt. The limited memory bandwidth of desktop CPUs, compared to server-grade processors found in HPC nodes with more memory channels, further exacerbates this issue, creating a data starvation problem for the available cores even if the problem technically “fits” in RAM.

Beyond core count and memory, other bottlenecks emerge. Storage performance on regular computing systems, typically single HDDs or SSDs, can be a limiting factor for simulations that generate large amounts of data (e.g., transient simulations writing results at frequent intervals) or require frequent checkpointing. The process of reading mesh files, writing solution data, and post-processing results can become painfully slow. Furthermore, the thermal design power (TDP) and cooling solutions in desktop systems are not intended for sustained 100% utilization of all cores and memory for extended periods, which is common for CFD workloads. This can lead to thermal throttling (where the CPU reduces its clock speed to prevent overheating), further degrading performance, or even causing system instability. For organizations relying on Ansys Fluent for critical engineering insights, these limitations mean an inability to tackle complex problems, a reliance on oversimplified models that may not reflect reality, and a significant competitive disadvantage. MR CFD often encounters clients struggling with these exact bottlenecks before they transition to HPC solutions.

These performance barriers highlight the necessity of a more powerful approach. Next, we will explore how HPC environments transform Ansys Fluent’s capabilities, unlocking its full simulation potential.

Ansys Fluent on HPC: Unlocking Simulation Potential

Transitioning Ansys Fluent workloads from regular computing to a High-Performance Computing (HPC) environment is not just an incremental improvement; it’s a transformative step that unlocks the full potential of this powerful Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) software. HPC addresses the core limitations of desktops and workstations by providing massive parallel computing resources, vast memory capacities, and high-speed communication and storage. This synergy allows engineers and researchers to tackle simulations of a scale and complexity previously unimaginable on standard hardware, leading to deeper insights, more accurate predictions, and accelerated innovation cycles. The ability to distribute a single, large CFD problem across hundreds or even thousands of processor cores in an HPC cluster dramatically reduces solution times, turning multi-day or multi-week simulations into overnight or few-hour runs. This speed-up enables more design iterations, parametric studies, and optimization workflows, ultimately leading to better-engineered products and more efficient processes.

The benefits of HPC for Ansys Fluent extend far beyond just raw speed. The significantly larger aggregated memory hierarchy available in HPC clusters allows for simulations with much finer mesh sizes. This increased mesh fidelity is crucial for accurately capturing intricate geometric details, resolving complex flow features like boundary layers, vortices, and shock waves, and improving the overall accuracy of the simulation results. For example, in aerospace, accurately predicting drag on an aircraft requires extremely fine meshes near the aircraft surface. In turbomachinery, resolving the flow through complex blade passages demands high cell counts. HPC makes such high-fidelity modeling feasible. Furthermore, HPC empowers the use of more sophisticated physical models within Ansys Fluent, such as advanced turbulence models (e.g., Large Eddy Simulation (LES) or Detached Eddy Simulation (DES)), detailed chemical reaction mechanisms, or multi-physics simulations involving fluid-structure interaction or electromagnetics. These models, while providing more realistic predictions, are often too computationally expensive for regular computing environments.

Real-world applications demonstrate this unlocked potential daily. Automotive companies use HPC with Ansys Fluent for detailed underhood thermal management simulations, optimizing component placement and cooling strategies. The process industry relies on HPC to simulate complex mixing and reaction kinetics in large-scale chemical reactors, improving yield and safety. In renewable energy, HPC is used to model airflow over entire wind farms to optimize turbine placement and maximize energy capture. MR CFD routinely guides clients in leveraging HPC to solve their most challenging CFD problems, enabling them to explore designs and phenomena that were previously out of reach. This might involve simulating the transient behavior of a new valve design under extreme conditions or performing a detailed aerodynamic analysis of a novel drone configuration. The common thread is that HPC empowers Ansys Fluent users to move beyond approximations and simplifications, tackling problems with the scale and complexity that truly reflect real-world conditions. This shift not only accelerates the time-to-solution but fundamentally enhances the quality and applicability of the simulation results.

One of the most immediate and impactful benefits of HPC for Ansys Fluent is its ability to handle incredibly complex geometries through massive mesh sizes. We will now delve deeper into this specific aspect.

The Mesh Size Factor: How HPC Handles Complex Geometries

The accuracy and fidelity of Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) simulations, particularly those performed with Ansys Fluent, are profoundly influenced by the mesh size and quality. The mesh, a discretization of the geometric domain into a multitude of small cells or elements, is where the governing fluid flow equations are solved. To accurately capture complex geometric features—such as intricate cooling channels in a turbine blade, the detailed vasculature in a biomedical flow model, or the myriad components in an automotive underhood—a very fine mesh with a high cell count is often required. Regular computing systems, with their limited memory and processing power, struggle immensely when faced with these massive meshes. Attempting to load, process, and solve a simulation with tens or hundreds of millions of cells on a desktop workstation will quickly exhaust available RAM, leading to excessive disk swapping and impractically long, if not impossible, solution times.

High-Performance Computing (HPC) fundamentally changes this equation by providing the necessary resources to manage and solve problems with enormous mesh sizes. The distributed memory architecture of HPC clusters is key. A mesh that is too large for a single node’s memory can be partitioned and distributed across many nodes, with each node holding and processing only a portion of the total mesh. For example, if a simulation requires a mesh leading to 500GB of memory footprint and each HPC node has 128GB of usable RAM, the problem could be distributed across 4-5 nodes (or more, depending on the solver’s parallel efficiency and specific memory usage). This domain decomposition is managed by Ansys Fluent’s parallel solver, which utilizes MPI (Message Passing Interface) for communication between nodes, allowing them to exchange boundary information for their respective mesh partitions. The high-bandwidth, low-latency network interconnects in HPC systems ensure that this inter-node communication is efficient, minimizing overhead and allowing the parallel computing power of the cluster to be effectively applied to the globally large mesh.

The practical implications are significant. Engineers using Ansys Fluent on HPC can tackle geometries of far greater complexity and detail than ever before. This means less need for de-featuring or oversimplifying CAD models, leading to simulations that more closely represent the actual physical product or process. For instance, simulating the aerodynamics of a complete vehicle, including wheels, mirrors, and underbody details, rather than a simplified exterior shell, becomes feasible. In manufacturing, the detailed flow through a complex injection mold can be analyzed to predict defects and optimize the process. MR CFD has extensive experience in guiding clients through the challenges of generating and solving these large meshes, demonstrating how HPC architectures directly enable higher fidelity simulations. The ability to handle meshes with hundreds of millions, or even billions, of cells is a game-changer, allowing for resolution of finer flow structures and ultimately leading to more reliable and insightful CFD results. This capability is not just about size, but about the complexity and realism that can be incorporated into simulations, pushing the boundaries of engineering analysis.

Handling large meshes is one part of the equation; the other is the time it takes to reach a converged solution. Next, we will quantify the dramatic reduction in solution convergence time achieved when moving Ansys Fluent workloads to HPC.

Convergence Time: From Days to Hours with HPC

One of the most compelling and quantifiable benefits of migrating Ansys Fluent simulations from regular computing to High-Performance Computing (HPC) is the dramatic reduction in solution convergence time. In Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD), convergence refers to the state where the iterative solution of the discretized flow equations stabilizes, and the residuals (a measure of the error in the equations) drop below a predefined tolerance. Reaching this converged state can require thousands or even hundreds of thousands of iterations, especially for complex, non-linear problems. On a regular computing system with limited cores, each iteration can take a significant amount of time, leading to overall simulation runtimes that stretch into days, weeks, or even months for challenging cases. This protracted timeframe severely hampers engineering productivity, limits the number of design explorations possible, and can delay critical project decisions.

HPC systems, with their massively parallel computing capabilities, drastically alter this scenario. By distributing the computational workload of Ansys Fluent across hundreds or thousands of processor cores (including GPU acceleration where applicable), the time taken for each iteration is significantly reduced. While perfect linear scalability (doubling the cores halves the time) is rarely achieved due to communication overhead and serial portions of the code (Amdahl’s Law), the speedups are nonetheless substantial. It’s common to see simulations that would take 72 hours on a high-end workstation complete in 4-6 hours on a moderately sized HPC cluster. This transformation from days to hours has a profound impact. Engineers can perform more simulations, explore a wider range of design parameters, conduct sensitivity studies, and undertake more comprehensive optimization tasks within tight project deadlines. For instance, an automotive engineer could evaluate ten different aerodynamic designs in the time it previously took to evaluate one, leading to a more optimized and efficient final product.

Consider a typical industrial CFD problem: simulating the external aerodynamics of a vehicle with a 20-million-cell mesh.

- Regular Computing (e.g., 16-core workstation):

- Time per iteration: ~30 seconds

- Iterations to converge: 5,000

- Total convergence time: 30s * 5000 = 150,000 seconds = ~41.6 hours (assuming it even fits in memory and runs stably)

- HPC (e.g., 256 cores on a cluster):

- Achievable speedup (conservative estimate): 10-12x over the 16-core workstation (actual speedup depends on problem specifics, interconnect, and Fluent version).

- Effective time per iteration: ~30s / 12 = ~2.5 seconds

- Total convergence time: 2.5s * 5000 = 12,500 seconds = ~3.47 hours

This example illustrates a more than 10-fold reduction in wall-clock time. MR CFD has benchmarked numerous Ansys Fluent cases demonstrating such speedups, enabling clients to meet aggressive timelines and make data-driven decisions faster. This acceleration is not merely a convenience; it’s a strategic advantage, allowing companies to innovate more rapidly and respond more effectively to market demands. The ability to obtain critical simulation results in hours instead of days or weeks fundamentally changes the way engineering design and analysis are conducted.

Beyond single-physics simulations, the advantages of HPC become even more pronounced when tackling the complexities of multi-physics simulations, which are often only practical with such resources.

13. Multi-physics Simulations: Only Practical with HPC Resources

Modern engineering challenges increasingly involve the interaction of multiple physical phenomena. Multi-physics simulations, which simultaneously model these coupled interactions, represent the cutting edge of computational analysis and are often essential for accurately predicting the behavior of complex systems. Ansys Fluent is capable of handling a wide range of multi-physics simulations, such as fluid-structure interaction (FSI) to analyze the deformation of a bridge under wind load, conjugate heat transfer (CHT) to model cooling of electronics, aeroacoustics to predict noise generated by airflow, or reacting flows with detailed chemical kinetics in combustion systems. While incredibly insightful, these simulations are significantly more computationally demanding than their single-physics counterparts. Each coupled physical domain introduces its own set of equations, variables, and often, its own mesh or solution requirements, leading to a substantial increase in overall problem size and complexity.

Attempting multi-physics simulations of any significant scale or fidelity on regular computing systems is often impractical or outright impossible. The combined memory footprint can easily exceed the capacity of even high-end workstations, and the computational load required to solve the coupled equation sets iteratively can lead to prohibitively long run times. For example, an FSI simulation needs to solve the fluid dynamics equations in Ansys Fluent and the structural mechanics equations (often in a separate solver like Ansys Mechanical), exchanging data (pressures, displacements) at the interface between the fluid and solid domains at each time step or coupling iteration. This involves not only the computational cost of each individual solver but also the overhead of data mapping and synchronization. The sheer number of calculations and the volume of data being exchanged make High-Performance Computing (HPC) an absolute necessity for obtaining meaningful results within a practical timeframe.

HPC environments provide the requisite ingredients for successful multi-physics simulations:

- Massive Parallelism: To concurrently solve the equations for different physics and across large computational domains.

- Large Memory Capacity: To accommodate the combined memory requirements of all involved physics models and their respective meshes.

- High-Speed Interconnects: Crucial for efficiently exchanging large amounts of data between different solver components or physics domains that might be running on different sets of nodes within the cluster computing environment.

- Robust Software Integration: The Ansys ecosystem, for instance, is designed to facilitate these coupled simulations, but it relies on the underlying HPC architecture to perform efficiently.

MR CFD has helped clients tackle complex multi-physics simulations using Ansys Fluent on HPC, such as optimizing the performance of electro-chemical devices by coupling fluid flow, heat transfer, and electrochemical reactions, or analyzing the thermal stresses in an engine component subjected to hot exhaust gases. These types of analyses provide a holistic understanding of product behavior that would be unattainable through isolated, single-physics models or with the limited resources of regular computing. The ability to perform these sophisticated, coupled simulations is a key differentiator offered by HPC, enabling engineers to design safer, more efficient, and more reliable products by capturing the intricate interplay of real-world physics.

The benefits for complex meshes, convergence times, and multi-physics are clear, but how does performance scale as problems get larger? We will now look at scaling considerations and why regular computing often fails.

Scaling Considerations: When Regular Computing Simply Cannot Cope

The concept of scalability is central to understanding the performance advantages of High-Performance Computing (HPC) over regular computing, especially for demanding applications like Ansys Fluent. Scalability in this context refers to how well a system’s performance increases as more computational resources (e.g., cores, nodes) are added to solve a larger problem or to solve a fixed-size problem faster (strong scaling vs. weak scaling). Regular computing systems, by their very architecture, exhibit poor or non-existent scalability beyond a very limited number of cores within a single machine. Once you’ve maxed out the cores on a desktop CPU (e.g., 8, 16, or perhaps 32 on a high-end workstation), there’s no path to further performance gains for a single, tightly-coupled simulation job. You simply cannot add more processors or memory beyond the physical limits of that single machine.

HPC clusters, however, are designed for scalability. By adding more nodes to the cluster, you increase the total available processing power, memory capacity, and often, aggregate I/O bandwidth. For Ansys Fluent simulations, this means that as the problem size (e.g., mesh size) increases, you can often maintain reasonable solution times by distributing the workload across a larger number of cores. Conversely, for a fixed problem size, increasing the number of cores can reduce the solution time, up to a point where communication overheads or serial portions of the code (as described by Amdahl’s Law) start to dominate. A common benchmark metric used to evaluate this is parallel efficiency, which measures how close the actual speedup on P processors is to the ideal P-times speedup. While perfect linear scaling is rare, well-optimized Ansys Fluent simulations on efficient HPC architectures with low-latency network interconnects can achieve good scaling (e.g., 70-90% parallel efficiency) up to hundreds or even thousands of cores for suitable problems.

Below is a conceptual comparison table illustrating scaling limitations:

| Feature / Scenario | Regular Computing (e.g., 16-core Workstation) | HPC (e.g., 1000-core Cluster) |

| Max Cores for 1 Job | 16 (or up to CPU max, e.g., 64) | 1000+ (limited by license, problem, interconnect) |

| Max Memory for 1 Job | Typically 64GB – 256GB | Terabytes (aggregated across nodes) |

| Handling Large Mesh | Severely limited, fails if exceeds RAM | Efficiently handles very large, distributed meshes |

| Strong Scaling Limit | Reached very quickly (e.g., 8-16 cores) | Can scale well to hundreds/thousands of cores |

| Time for 50M Cell Sim | Potentially days/weeks (if possible at all) | Hours |

| Time for 500M Cell Sim | Impossible | Feasible, potentially hours/day(s) |

These scaling capabilities are not just theoretical. MR CFD regularly conducts scaling studies for clients to determine the optimal number of cores for their specific Ansys Fluent models, balancing cost (license fees, compute time) against desired turnaround time. For example, a simulation might scale well up to 512 cores, but beyond that, the speedup diminishes, making 512 cores the “sweet spot” for that particular job on that specific HPC system. Regular computing simply doesn’t offer this flexibility or power. When a simulation model grows in complexity or size, or when faster turnaround is needed, users of regular computing hit a hard wall. HPC provides the pathway to overcome these limitations, enabling the solution of problems that are orders ofmagnitude larger and more complex than what regular computing can ever hope to address. This capacity to scale is fundamental for tackling grand-challenge engineering problems and driving innovation.

Given the clear performance benefits, a crucial question arises: is the investment in HPC resources justified for your specific Ansys Fluent simulation needs? This leads us to a cost-benefit analysis.

Cost-Benefit Analysis: Is HPC Worth It for Your Fluent Simulations?

The decision to invest in or utilize High-Performance Computing (HPC) resources for Ansys Fluent simulations is a significant one, involving careful consideration of costs versus benefits. While HPC offers undeniable advantages in terms of speed, scale, and the ability to tackle complex problems, these capabilities come with associated expenses, whether for on-premises systems (hardware acquisition, maintenance, power, cooling, specialized staff) or cloud HPC services (pay-per-use compute instances, storage, data transfer). The core question for any organization is whether the value derived from using HPC—such as accelerated product development, improved product performance, reduced physical prototyping costs, or enhanced research outcomes—outweighs these investments. For many engineering firms and research institutions relying on Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD), the answer is increasingly a resounding “yes,” especially as simulation complexity grows and time-to-market pressures intensify.

To conduct a meaningful cost-benefit analysis, several factors should be evaluated:

- Simulation Throughput and Turnaround Time: How many simulations are needed, and how quickly must results be obtained? If regular computing leads to lengthy queues or simulation times that delay critical project milestones, the cost of these delays (missed opportunities, extended development cycles) can quickly exceed HPC costs. The ability of HPC to reduce convergence time from days to hours, as previously discussed, can translate directly into faster product development and quicker response to market needs.

- Simulation Fidelity and Accuracy: Are current regular computing limitations forcing oversimplification of models (e.g., coarser mesh sizes, simpler physics) that compromise the accuracy and reliability of the simulation results? The cost of making poor design decisions based on inaccurate simulations can be substantial, including redesign efforts, product failures, or safety issues. HPC enables higher-fidelity simulations that provide more trustworthy insights.

- Complexity of Problems: Are you looking to tackle problems that are simply impossible on regular computing, such as large-scale transient simulations, detailed multi-physics simulations, or extensive design of experiments (DoE) studies? The value of insights gained from these advanced simulations, which might lead to breakthrough innovations or significant performance improvements, can be immense.

- Cost of Physical Prototyping and Testing: High-fidelity CFD simulations on HPC can significantly reduce the need for expensive and time-consuming physical prototypes and tests. If each physical prototype costs tens or hundreds of thousands of dollars, and HPC simulations can reduce the number of prototypes required by even one or two, the savings can be substantial.

- Staff Productivity and Innovation: When engineers are not waiting for simulations to complete, they can spend more time on analysis, design iteration, and innovation. The frustration and inefficiency caused by slow computational tools can be a hidden cost. HPC can empower engineers to explore more design options and push the boundaries of what’s possible.

MR CFD often assists clients in this evaluation process, helping them quantify the return on investment (ROI) from adopting HPC for their Ansys Fluent workloads. For example, if reducing the design cycle of a new product by two months (achieved through faster simulations on HPC) allows a company to capture an additional $X million in early market revenue, this benefit can be directly weighed against the HPC expenditure. Furthermore, the cost of Ansys Fluent licenses themselves can be a factor; ensuring these expensive licenses are used efficiently on performant hardware maximizes their value. For many scenarios, particularly those involving complex geometries, advanced physics, or demanding turnaround times, the strategic benefits and long-term cost savings offered by HPC make it a compelling and often essential investment rather than a luxury.

Once the need for HPC is established, a new decision arises: whether to invest in on-premises infrastructure or leverage cloud-based HPC offerings. This is the new decision matrix we will explore next.

Cloud HPC vs. On-Premises: The New Decision Matrix

Once an organization recognizes the necessity of High-Performance Computing (HPC) for its Ansys Fluent workloads, a critical strategic decision emerges: whether to invest in an on-premises HPC cluster or to utilize cloud-based HPC resources. Both models offer distinct advantages and disadvantages, and the optimal choice depends on specific usage patterns, budget constraints, IT capabilities, and strategic priorities. The traditional approach involved procuring, housing, and managing an in-house cluster computing facility. This requires significant upfront capital expenditure (CapEx) for servers, network interconnects, storage, power, and cooling infrastructure, as well as ongoing operational expenditure (OpEx) for maintenance, software licenses, energy consumption, and skilled IT personnel to manage the complex environment. The primary benefits of on-premises HPC include greater control over the hardware and software stack, potentially lower long-term costs for very high and consistent utilization, and enhanced data security and sovereignty if sensitive data must remain within the organization’s physical perimeter.

Cloud HPC, offered by providers like AWS, Azure, Google Cloud, and specialized HPC cloud services, presents a compelling alternative, transforming HPC access into an operational expense (OpEx) model. Users can provision and de-provision HPC resources on demand, paying only for what they use. This offers tremendous flexibility and scalability, allowing organizations to access virtually unlimited computational power without upfront hardware investment. Cloud platforms provide a wide variety of instance types, including those with powerful CPUs, the latest GPU acceleration, and high-speed interconnects, often pre-configured for CFD workloads like Ansys Fluent. Key advantages of cloud HPC include:

- Accessibility and Agility: Rapid access to cutting-edge hardware without lengthy procurement cycles.

- Scalability on Demand: Easily scale up resources for peak demands (e.g., large mesh sizes, urgent projects) and scale down when not needed, optimizing cost.

- Reduced Management Overhead: The cloud provider handles hardware maintenance, infrastructure updates, and physical security, freeing up internal IT resources.

- Global Reach: Access compute resources in different geographical regions, potentially closer to collaborators or data sources.

However, cloud HPC also has considerations. Data transfer costs for large input and output files can be significant. For continuous, high-volume workloads, the cumulative operational costs of cloud HPC might eventually exceed the amortized cost of an on-premises system. Software licensing in the cloud (e.g., for Ansys Fluent) also needs careful management; while some providers offer pay-as-you-go licensing, others require bring-your-own-license (BYOL) models. Security in the cloud, while robust, requires adherence to best practices and understanding the shared responsibility model. MR CFD has experience deploying and optimizing Ansys Fluent in both on-premises and various cloud environments, helping clients navigate this decision matrix. Factors like burst capacity needs (favoring cloud), steady baseline workloads (potentially favoring on-premises for cost at scale), IT expertise, and capital availability all play crucial roles. Increasingly, hybrid approaches are also emerging, where organizations use on-premises systems for baseline loads and burst to the cloud for peak demands, offering a balance of control and flexibility.

Whether you opt for on-premises, cloud, or a hybrid approach, getting started with HPC for Ansys Fluent involves understanding some essential requirements. This will be our focus in the next section.

Getting Started with HPC for Ansys Fluent: Essential Requirements

Embarking on the use of High-Performance Computing (HPC) for Ansys Fluent simulations can seem daunting, but understanding the essential requirements can smooth the transition and ensure you build or select an environment that truly meets your Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) needs. Whether you are considering an on-premises cluster or leveraging cloud HPC resources, several key components must be carefully evaluated. These include processor choice, memory configuration, network infrastructure, storage solutions, and the software environment. Failing to adequately specify any of these can lead to an underperforming system that doesn’t deliver the expected speedups or scalability for your demanding Ansys Fluent workloads. It’s not just about acquiring the most expensive hardware; it’s about creating a balanced architecture where no single component becomes a critical bottleneck for the types of simulations you intend to run.

Firstly, processor selection is crucial. For Ansys Fluent, CPUs with high clock speeds, a good number of cores per socket (though not necessarily the absolute maximum, as per-core performance and memory bandwidth per core are also vital), and large L3 caches are generally preferred. Modern Intel Xeon Scalable processors or AMD EPYC series CPUs are common choices. Increasingly, GPU acceleration is also a significant consideration for specific Fluent solvers and parts of the workflow that are amenable to GPU offloading, potentially offering substantial speedups. Secondly, memory (RAM) capacity and bandwidth are paramount. CFD simulations are notoriously memory-intensive. A good rule of thumb is to have at least 4GB to 8GB of RAM per physical CPU core, but for very large mesh sizes or complex physics, this may need to be higher, potentially 16GB/core or more. High-bandwidth memory with multiple channels per CPU is essential to feed the cores efficiently. Thirdly, the network interconnect is critical for multi-node simulations. For clusters of more than a few nodes, a low-latency, high-bandwidth interconnect like InfiniBand (e.g., NDR, HDR) or high-speed Ethernet (e.g., 100/200 Gbps RoCE) is indispensable for good parallel scaling in Ansys Fluent.

Fourthly, storage solutions must provide sufficient capacity and I/O performance to handle large mesh files, solution data, and checkpoint files. A parallel file system (e.g., Lustre, BeeGFS, IBM Spectrum Scale) is often recommended for on-premises HPC clusters to provide high-throughput, concurrent access from all compute nodes. For cloud HPC, providers offer various high-performance storage tiers. Finally, the software stack includes the operating system (typically a Linux distribution like Rocky Linux, AlmaLinux, or RHEL), job schedulers (e.g., Slurm, PBS Pro), MPI libraries compatible with Ansys Fluent, and of course, the Ansys Fluent software itself, along with appropriate licensing.

For specific guidance and tailored HPC for ansys fluent solutions, resources like the MR CFD portal at https://portal.mr-cfd.com/hpc can provide invaluable insights and services.

Understanding these requirements allows organizations to make informed decisions, ensuring their HPC investment effectively accelerates their simulation capabilities.

Minimum Specifications for Different Classes of Fluent Simulations (Conceptual):

| Simulation Class | Est. Mesh Size | Min. Cores | Min. RAM/Node | Recommended Interconnect | Storage Type |

| Small/Moderate | 1M – 10M cells | 16 – 64 | 64GB – 128GB | Gigabit/10G Ethernet | Local SSD/Fast NAS |

| Medium/Large | 10M – 50M cells | 64 – 256 | 128GB – 256GB | InfiniBand / 100G+ RoCE | Parallel File System |

| Very Large/Complex | 50M – 500M+ cells | 256 – 1000+ | 256GB – 512GB+ | InfiniBand / 200G+ RoCE | Parallel File System |

| GPU Accelerated | Varies | CPU + 2-8 GPUs/Node | 128GB – 256GB (CPU RAM) | InfiniBand / NVLink | Parallel File System |

Note: These are general guidelines; actual requirements depend heavily on specific physics, solver settings, and desired turnaround time. RAM is often the primary constraint for mesh size.

Having outlined the essential hardware and software requirements, the next step is to ensure that Ansys Fluent itself is properly configured and optimized to take full advantage of these powerful HPC environments.

Optimizing Ansys Fluent for HPC Environments

Deploying Ansys Fluent on a High-Performance Computing (HPC) system is the first step; unlocking its maximum potential requires careful optimization and configuration tailored to the specific HPC architecture and the nature of the Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) problems being solved. Simply running Ansys Fluent with default settings on an HPC cluster may not yield the best possible performance or scalability. Technical best practices involve understanding how Fluent interacts with the underlying hardware—processors, memory hierarchy, network interconnects, and storage—and adjusting parameters and workflows accordingly. This optimization process can significantly reduce convergence time, improve resource utilization, and ultimately enhance the return on investment from your HPC infrastructure and Ansys Fluent licenses. Effective optimization is a continuous process, especially as software versions, hardware, and simulation complexity evolve.

One of the primary areas for optimization is parallel performance. This involves selecting the appropriate parallel processing method (e.g., shared memory with threads, distributed memory with MPI, or a hybrid approach) and determining the optimal number of cores or nodes for a given simulation. Ansys Fluent provides various partitioning schemes to distribute the mesh across parallel processes; choosing the right scheme (e.g., METIS, Principal Axes) can impact load balance and inter-process communication overhead. It’s crucial to conduct scaling studies to identify the sweet spot where adding more cores still provides significant speedup without being negated by communication bottlenecks. For GPU acceleration, ensuring that the GPU-accelerated solvers are used for applicable physics and that data transfer between CPU and GPU is minimized are key considerations. Job schedulers in HPC environments (like Slurm or LSF) also need to be configured correctly to allocate resources efficiently and ensure Fluent jobs are launched with appropriate MPI settings and process pinning (binding processes to specific cores) to maximize performance and avoid contention, especially in NUMA architectures.

Beyond parallel settings, I/O performance can be a significant factor, particularly for large transient simulations or when writing frequent checkpoint files. Optimizing I/O involves choosing appropriate file types, adjusting write frequencies, and leveraging parallel I/O capabilities if supported by Ansys Fluent and the underlying parallel file system. Memory usage optimization is also critical. While HPC systems offer large memory capacities, efficient memory management within Fluent can still improve performance and allow for larger problem sizes. This might involve choices in discretization schemes or solver settings that have different memory footprints. MR CFD specializes in these types of optimizations, working with clients to profile their Ansys Fluent workloads, identify bottlenecks, and implement best practices. This can include tuning solver settings (e.g., algebraic multigrid (AMG) controls, Courant number), selecting optimal discretization schemes, and developing scripted workflows for efficient job submission and management on HPC clusters. For example, using asynchronous I/O or adjusting the aggressiveness of the AMG solver can yield noticeable performance improvements for specific types of simulations.

Bash # Example: Basic Slurm submission script for Ansys Fluent # (Illustrative - specific flags and modules depend on local HPC setup and Fluent version) #!/bin/bash #SBATCH --job-name=fluent_simulation #SBATCH --nodes=4 #SBATCH --ntasks-per-node=32 # Requesting 32 cores per node #SBATCH --cpus-per-task=1 #SBATCH --mem-per-cpu=4G # Memory per CPU core #SBATCH --time=24:00:00 # Max walltime #SBATCH --partition=compute # Specify the partition/queue # Load Ansys Fluent module (specific to HPC environment) module load ansys/2023R1 # Or your specific version # Define input file and journal file JOURNAL_FILE="my_simulation.jou" CASE_FILE="my_case.cas.h5" # Or .cas # Set Fluent launch command (example for Intel MPI) # Adjust -t<cores> to total cores (nodes * ntasks-per-node) # The exact MPI flavor and launch options might vary (e.g., -mpi=ibmmpi, -mpi=openmpi) FLUENT_COMMAND="fluent 3ddp -g -t128 -mpi=intelmpi -affinity=off -ssh -cnf=$SLURM_NODELIST -i $JOURNAL_FILE > fluent_output.log" # Note: Fluent's built-in mechanisms for distributing across nodes listed in $SLURM_NODELIST are often used. # The -cnf flag passes the list of allocated nodes. # The -t flag specifies the total number of parallel processes. echo "Starting Fluent simulation: $CASE_FILE" echo "Using journal file: $JOURNAL_FILE" echo "Running on nodes: $SLURM_NODELIST" echo "Total cores: $SLURM_NTASKS" # Run Fluent eval $FLUENT_COMMAND echo "Fluent simulation finished."

This sample script illustrates some common parameters, but a truly optimized setup often involves more detailed MPI tuning, environment variable settings, and Fluent-specific command-line arguments. Through such meticulous tuning and workflow adjustments, the true power of HPC for Ansys Fluent can be harnessed.

After exploring the intricacies of HPC, its advantages for Ansys Fluent, and the practicalities of implementation and optimization, it’s time to synthesize these insights. The conclusion will provide clear guidance on making the right computing choice for your specific simulation needs.

Conclusion: Making the Right Computing Choice for Your Simulation Needs

The journey from understanding the fundamental distinctions between High-Performance Computing (HPC) and regular computing to appreciating its profound impact on demanding applications like Ansys Fluent reveals a clear imperative: for complex, large-scale, or time-critical Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) simulations, HPC is not a luxury but a necessity. Regular computing, encompassing standard desktops and workstations, serves admirably for a vast range of tasks but inevitably hits a performance wall when faced with the multi-million cell mesh sizes, intricate physics, and extensive iteration counts inherent in modern CFD. The architectural advantages of HPC—massively parallel computing capabilities, sophisticated memory hierarchies, high-bandwidth network interconnects, and scalable storage solutions—are precisely what Ansys Fluent requires to tackle challenging simulations effectively, reducing convergence times from days or weeks to mere hours.

We’ve seen how HPC environments enable the use of finer meshes for greater accuracy, facilitate complex multi-physics simulations that are impractical on lesser hardware, and provide the scalability needed as simulation complexity grows. The decision to transition to HPC involves a cost-benefit analysis, but for many organizations, the value derived from faster design cycles, improved product performance, reduced physical prototyping, and the ability to innovate beyond the constraints of regular computing provides a compelling return on investment. Whether opting for on-premises clusters, flexible cloud HPC offerings, or a hybrid approach, the key is to align the chosen solution with specific simulation requirements, from core counts and memory to interconnect speed and storage performance. Furthermore, optimizing Ansys Fluent itself for the chosen HPC environment through careful parameter tuning, efficient parallel strategies, and streamlined workflows is crucial to maximizing throughput.

Ultimately, making the right computing choice depends on a thorough assessment of your current and future simulation needs. If your Ansys Fluent simulations are characterized by:

- Long runtimes that impede productivity and delay projects.

- A need for mesh sizes or physical model complexity that exceeds the memory or processing capacity of your current systems.

- The requirement to run numerous design variations or optimizations within tight deadlines.

- A desire to tackle advanced multi-physics simulations. Then, a transition to HPC is strongly indicated. MR CFD stands as a trusted advisor in this journey, offering deep expertise in both Ansys Fluent and HPC architectures. We can help you navigate the complexities of selecting, implementing, and optimizing HPC solutions, ensuring that you harness the full computational power needed to drive innovation and achieve your engineering goals. The era of relying solely on regular computing for serious CFD work is rapidly closing; embracing HPC is key to staying at the forefront of computational engineering.

Comments (0)