The Courant Number (CFL) Explained: A Guide for Stable Transient Simulations

As a Senior CFD Educator with over a decade spent guiding engineers through the complexities of Ansys Fluent, I’ve seen countless simulations fail. The most common culprit? A misunderstanding of one fundamental parameter: the Courant Number. In my 10 years of CFD consulting, I can confidently say that at least 70% of initial transient divergence cases trace back to CFL mismanagement.

This courant number guide is designed to demystify the Courant-Friedrichs-Lewy (CFL) condition once and for all. We will move beyond the simple formula to understand its physical meaning, its practical application in Ansys Fluent, and the advanced strategies experts use to ensure their simulations are not just stable, but accurate. By the end of this article, you will have a clear framework for setting the perfect timestep, troubleshooting divergence, and achieving robust results in your unsteady flow simulations.

What Is the Courant Number and Why Does It Control Your Simulation Stability?

At its core, the Courant Number represents a physical speed limit for information transfer within your computational mesh. Imagine your simulation domain is a grid of city blocks (your cells) and information (like pressure or velocity changes) is a delivery truck. The timestep, which we’ll call delta-t, is the time you allow the truck to travel before you check its location again.

The CFL condition dictates that this delivery truck cannot travel further than one city block in a single time step.

“Think of CFL as the speed limit for your simulation—exceed it, and you crash.”

Why? Because CFD solvers calculate the properties of a cell (e.g., pressure, velocity) at the next time step based on the information from its immediate neighbors at the current time step. If a piece of information (like a pressure wave) travels across an entire cell and into the next one within a single timestep, the solver in the origin cell never gets a chance to “see” it. This leads to a mathematical breakdown where the solution becomes unbounded—what we see as divergence, with residuals skyrocketing to infinity.

For explicit time-stepping schemes, this limit is strict: the Courant number must be less than or equal to 1 (written as CFL <= 1). Ansys Fluent’s implicit solvers offer more leeway, but the underlying physical principle remains the same. Ignoring the CFL number is like telling your solver to solve a problem with missing information, leading inevitably to instability.

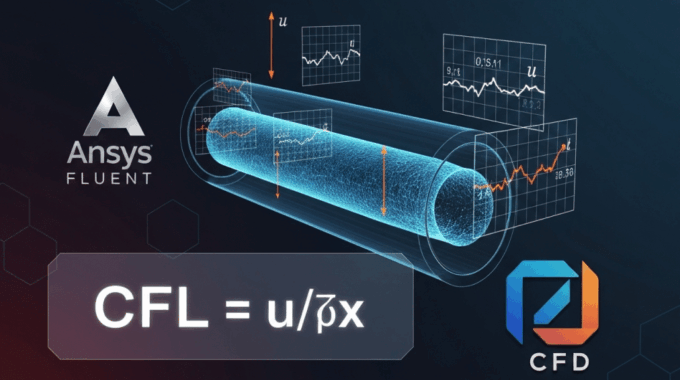

How Do You Derive the Courant Number Formula from First Principles?

To truly grasp the CFL condition, let’s look at its mathematical roots. It originates from the numerical analysis of simple hyperbolic partial differential equations, the most basic of which is the 1D linear advection equation. In plain text, it’s written as:

d(phi)/d(t) + u * d(phi)/d(x) = 0

This equation describes a quantity “phi” being transported (advected) with a constant velocity “u”. The d()/d() terms represent partial derivatives. When we discretize this equation, we are approximating these derivatives.

The time derivative, d(phi)/d(t), is approximated as: (phi at next timestep - phi at current timestep) / delta-t

The spatial derivative, d(phi)/d(x), is approximated as: (phi in current cell - phi in upstream cell) / delta-x

Substituting these into the advection equation reveals that the value of “phi” at the next timestep depends on a critical group of terms: (u * delta-t) / delta-x.

This term is the Courant Number. For the numerical scheme to be stable, a mathematical analysis shows that we must have:

CFL = (u * delta-t) / delta-x <= 1

This simple relationship shows the direct link between the physical velocity (u), the chosen time step size (delta-t), and the mesh cell size (delta-x).

In a 3D simulation, this extends to include all velocity components:

CFL = delta-t * ( |u|/delta-x + |v|/delta-y + |w|/delta-z )

Here, |u|, |v|, and |w| are the absolute velocities in the x, y, and z directions, and delta-x, delta-y, and delta-z are the cell lengths in those directions. This fundamental principle ensures that our numerical method respects the physical propagation of information, forming the bedrock of transient simulation timestep calculation.

What Is the CFL Formula for Incompressible vs. Compressible Flows?

The core difference between incompressible and compressible flows is the presence of sound waves. In compressible flows, information propagates not just at the fluid velocity (u) but also at the speed of sound (c). The solver must account for the fastest-moving piece of information.

For Incompressible Flow: The information speed is simply the fluid velocity. CFL_incompressible = (|u| * delta-t) / delta-x

- Example (Mach 0.3): Water flowing at 10 m/s through a pipe with 1 mm cells. The speed of sound is ~1500 m/s. Since the flow velocity is much smaller, we only care about the fluid speed.

For Compressible Flow: The information speed is the sum of the fluid velocity and the local speed of sound. CFL_compressible = ((|u| + c) * delta-t) / delta-x

- Example (Mach 2): Air flowing at 680 m/s over an airfoil with 1 mm cells, where the speed of sound is 340 m/s. The relevant speed for the CFL number formula for compressible flow is the sum, 1020 m/s, which is significantly higher and demands a much smaller timestep. Ignoring the speed of sound here is a guaranteed recipe for divergence.

How Does the CFL Number Change with Turbulence Models?

This is a subtle but important point that many beginners miss. The turbulence model you choose can influence your timestep stability.

- RANS models (k-ε, k-ω SST): These models add source and sink terms to the transport equations that are often treated implicitly by the solver. This implicitness provides a stabilizing effect, often allowing you to use slightly higher Courant numbers without divergence.

- Scale-Resolving Simulations (LES, DES): These models are a different story. They aim to resolve the turbulent eddies directly. Consequently, they demand a strict CFL condition, typically requiring CFL < 1 (and often closer to 0.5) to maintain both stability and accuracy. In our advanced MR CFD transient analysis training, we dedicate an entire module to setting up robust LES simulations where CFL management is paramount.

Now that we understand the theory, let’s bridge the gap to practical application within the Ansys Fluent environment.

What CFL Values Should You Use in Ansys Fluent for Different Solvers?

The theoretical limit of CFL=1 is most relevant for explicit solvers. Ansys Fluent, however, primarily uses implicit vs explicit time stepping schemes, which gives us significantly more flexibility. An implicit solver is more stable, but that stability is not infinite for the complex, non-linear equations we solve in CFD.

Here is a practical decision table based on my experience training hundreds of engineers:

How Do You Set the Timestep in Fluent’s Pressure-Based Transient Solver?

For the most common solver, the pressure-based transient solver, you set the Time Step Size (delta-t) directly, not the Courant number. You must calculate it first.

Here’s the workflow:

- Estimate Key Values:

- Maximum expected velocity, u_max (m/s).

- Minimum cell size in the direction of flow, delta-x_min (m).

- Choose a Target CFL: Start conservatively. A target CFL of 0.5 to 1.0 is a robust starting point.

- Calculate delta-t: Use the rearranged formula: delta-t = (CFL_target * delta-x_min) / u_max

⚙️ Worked Example: Let’s simulate water flow in a pipe with a maximum velocity of 5 m/s. After meshing, we find our smallest cell size is 1 mm (0.001 m). We choose a conservative target CFL of 0.5.

delta-t = (0.5 * 0.001 m) / (5 m/s) = 0.0001 s

In Ansys Fluent, you would navigate to Solution > Run Calculation and enter 0.0001 into the Time Step Size field. This is a core skill taught in our Ansys Fluent time step size tutorial.

How Do You Enable Adaptive Timestepping in Fluent?

For simulations where the velocity changes dramatically (e.g., a valve slamming shut), a fixed timestep is inefficient. This is where adaptive timestep CFD becomes invaluable.

To enable it in Fluent:

- Navigate to

Solution > Solution Controls. - Under the

Solvertab, find and enable Adaptive Time Stepping. - The key setting is the Truncation Error Tolerance. The default value of 0.01 is often a good starting point.

- You must also set minimum and maximum allowable timesteps to bound the solver.

Pros:

- 🚀 Efficiency: Uses small steps only when needed, and larger steps when the flow is quasi-steady.

- Robustness: Can automatically reduce the timestep to navigate tricky, high-gradient events without diverging.

Cons:

- Oversight: Can sometimes overshoot critical transient events if the maximum step size is set too large.

- Complexity: Adds another layer of settings that needs to be understood.

I recommend using adaptive timestepping for multiphase and reacting flows.

How Do You Calculate the Optimal Timestep for Your Specific Geometry?

Calculating the perfect timestep isn’t a black art; it’s a systematic process. Here at MR CFD, we’ve refined this into a 5-step workflow that we use in our MR CFD consulting services for transient CFD.

- Step 1: Identify the Smallest Controlling Cell Size (delta-x_min)

- Go to

Mesh > Info > Sizein Fluent’s Meshing application orDomain > Mesh Infoin Fluent. Find the minimum cell size. This is your critical delta-x.

- Go to

- Step 2: Estimate the Maximum Characteristic Velocity (u_max)

- This is the fastest-moving phenomenon. For a single-phase flow, it’s the maximum fluid velocity. For a compressible flow, it’s (u_max + c). You can estimate this from your boundary conditions.

- Step 3: Choose a Conservative Target CFL

- Don’t be a hero. Start with a Courant number of 1. You can always increase it later. For LES or high-fidelity simulations, start with 0.5.

- Step 4: Compute the Initial Timestep (delta-t)

- Use the formula: delta-t = (CFL * delta-x_min) / u_max.

- Step 5: Test and Verify

- Run the simulation for just 10-20 timesteps. Watch the residuals. If stable, you can proceed. If it diverges, halve your delta-t and try again.

✅ Action Item: To make this process seamless, subscribe to our newsletter to download a free Excel calculator that performs these steps for you.

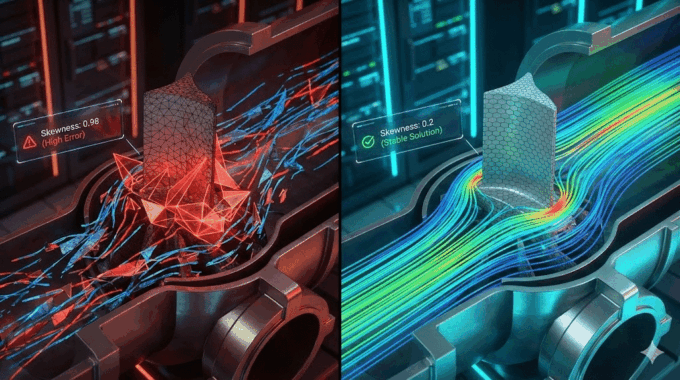

What Role Does Mesh Quality Play in CFL Stability?

Your mesh is the foundation of your simulation, and a poor mesh can shatter stability regardless of your timestep.

- High Aspect Ratio Cells: Long, skinny cells (aspect ratio > 100:1) are challenging. The CFL condition is limited by the smallest dimension. This can lead to an extremely small and impractical delta-t.

- Skewness: Highly skewed cells (skewness > 0.85) can cause local CFL violations and lead to divergence even when the global average CFL seems acceptable.

How Do You Handle CFL in Moving Mesh and Overset Simulations?

When the mesh itself is moving, the CFL calculation must be modified. The relative velocity between the fluid and the mesh is what matters.

The formula becomes: CFL = (|u_fluid – u_mesh|) * delta-t / delta-x

In practice, this means for Fluent dynamic mesh zones, you need a significantly more conservative timestep. I typically recommend starting with a CFL 30-50% lower than in a comparable static mesh case.

What Are the Common Mistakes Engineers Make with Courant Numbers?

After reviewing hundreds of client cases, I see the same preventable mistakes repeatedly. Avoid these pitfalls:

- Trusting the Global CFL: A simulation can have a global CFL of 10 but diverge because a few tiny, skewed cells have a local CFL of 500. Always check local values by plotting contours of the CFL number.

- Forgetting the Speed of Sound: This is the #1 mistake in compressible flow simulations. Remember the

(|u| + c)term! - Over-relying on Implicit Solvers: Just because an implicit solver can run with a CFL of 100 doesn’t mean it should. At very high Courant numbers, you introduce significant temporal error, smearing out transient details.

- Not Updating delta-t After Remeshing: If you refine your mesh, your delta-x_min decreases. If you forget to reduce your delta-t accordingly, you have inadvertently increased your CFL number.

How Do You Diagnose CFL-Related Divergence in Fluent?

When your simulation crashes, how do you confirm it’s a CFL issue?

- Monitor Residuals: The classic sign is residuals that suddenly spike to

1e+06or higher. - Plot CFL Contours: Go to

Solution > Graphics > Contours, and selectCell Courant Number. This will instantly show you the hotspot—the region of your domain that is violating the stability limit. - Use the TUI (Text User Interface): The command

/solve/monitors/surface/set-courant-monitorallows you to monitor the maximum CFL number in a specific cell zone.

Troubleshooting Flowchart: Divergence Occurs -> Reduce delta-t by 5x -> Run Again

- If Stable: Your CFL was too high.

- If Still Divergent: The issue is likely the mesh.

Plot CFL Contours->Identify High-CFL Cells->Refine/Improve Mesh Quality in that Region.

How Can You Implement Advanced CFL Strategies for Complex Physics?

For cutting-edge simulations, a one-size-fits-all approach to CFL doesn’t work.

- Multiphase (VOF): Requires a very low CFL, often around 0.25, to maintain a crisp interface.

- Combustion/Reacting Flows: You must ensure your timestep is small enough to resolve both the fluid dynamics and the chemical kinetics.

- Supersonic/Hypersonic Flows: In Ansys Fluent’s density-based solver, you can enable Local Timestepping to accelerate a steady-state solution, which provides a robust initial condition for a transient hypersonic case.

What Is the Relationship Between CFL and Numerical Diffusion?

While a high CFL causes divergence, an overly small timestep can harm your accuracy through numerical diffusion. Each time step you take introduces a tiny amount of numerical error. If you take an excessive number of steps, these errors accumulate, smearing out sharp gradients. The goal is to find a balance: a Courant number that is low enough for stability but not so low that you waste computational resources.

How Do You Use UDFs to Enforce Local CFL Limits?

For the ultimate control, you can use a User-Defined Function (UDF) to dynamically adjust the global timestep. A DEFINE_ADJUST UDF can loop over all cells, calculate the local CFL, find the maximum, and then adjust the next timestep accordingly.

Here’s a conceptual snippet of what that looks like in C code:

/* Sample UDF to control timestep based on max CFL */

#include "udf.h"

DEFINE_ADJUST(adjust_timestep, domain)

{

real max_cfl = 0.0;

real target_cfl = 0.8;

/* ... loop over all cell threads and cells ... */

/* ... compute cell_cfl for each cell ... */

/* ... update max_cfl if cell_cfl > max_cfl ... */

if (max_cfl > 0.0)

{

/* Get current timestep */

real current_dt = CURRENT_TIMESTEP;

/* Adjust for next step */

Set_Time_Step(target_cfl / max_cfl * current_dt);

}

}

This provides programmatic control that is far more precise than the built-in adaptive methods.

What Tools and Resources Can Help You Master CFL Management?

Mastering the Courant number is a journey, but you don’t have to go it alone.

- Free MR CFD CFL Calculator: We’ve built an Excel spreadsheet that calculates the required timestep. Subscribe to our newsletter to get your free copy.

- Ansys Help Documentation: The official documentation is an authoritative source.

- MR CFD’s “Transient CFD Mastery” Course: This comprehensive course provides hands-on tutorials covering everything from basic CFL setup to advanced UDF control.

- MR CFD LinkedIn Group: Join our community of over 5,000 CFD engineers to ask questions and get peer support.

How Does MR CFD Help Engineers Achieve Stable Transient Simulations?

Beyond training, we provide direct, expert intervention to solve your most challenging problems.

- Consulting for Divergence Troubleshooting: We offer a 24-hour turnaround service to diagnose your case file and provide actionable settings to fix it.

- Custom Training Workshops: We can tailor a workshop for your engineering team focused specifically on your applications.

- HPC Cluster Access: Run your transient simulations on our optimized high-performance computing clusters.

A recent client in the automotive sector had this to say:

“Our transient underhood thermal simulation kept diverging. We were stuck for weeks. MR CFD identified a local CFL violation due to poor mesh quality. Their recommendations reduced our simulation time by 60% and finally got us stable, accurate results.”

Frequently Asked Questions About the Courant Number

What happens if my CFL number exceeds 1 in an implicit solver?

Implicit solvers won’t necessarily diverge immediately. However, the temporal accuracy of your simulation will degrade. As you increase the CFL, you are essentially averaging information over a larger time interval, which can smear out or completely miss short-lived physical events. For time-accurate results, it is best practice to keep the CFL below 10.

Can I use a constant timestep for all transient simulations?

No, this is often inefficient. A constant timestep is suitable for flows that have reached a periodic state, like vortex shedding. For simulations with widely varying timescales—such as a valve opening—adaptive timestepping is far superior, saving significant computational time.

How do I choose between first-order and second-order time discretization?

You should almost always use the Second Order Implicit scheme for time discretization. It provides significantly better accuracy. The first-order scheme is more robust, making it useful for the first few timesteps of a difficult simulation to establish a stable flow field before switching to second-order.

What is the difference between global and local CFL numbers?

The global CFL is an average or maximum across your domain, while the local CFL is the value in each cell. A simulation can diverge due to a high local CFL in a tiny region even if the global CFL appears safe. Always plot contours of the Cell Courant Number to find local hotspots.

How does the CFL condition apply to LES and DNS?

For Large Eddy Simulation (LES) and Direct Numerical Simulation (DNS), adhering to the CFL condition is non-negotiable. These methods require a strict limit, typically CFL <= 1, and often practitioners aim for CFL approx 0.5-0.7 for high-fidelity results.

Can MR CFD review my Fluent setup to optimize CFL settings?

Yes, absolutely. This is a core part of our MR CFD consulting services. We can securely review your Fluent case files and provide a detailed report with specific recommendations for your timestep, mesh, and solver tuning, typically within 48 hours.

What is the CFL limit for multiphase flows in Ansys Fluent?

The limit depends on the model:

- Volume of Fluid (VOF): Requires a very low CFL, typically CFL <= 0.25, to maintain a sharp interface.

- Eulerian Model: Can generally tolerate CFL <= 1.

- Mixture Model: Can often run with CFL <= 5.

How do I calculate CFL for non-Newtonian fluids?

The formula is the same, based on velocity, cell size, and timestep. The challenge is in accurately predicting the maximum velocity (u_max) for fluids that exhibit complex shear thinning or shear thickening behavior.

Where can I download a free CFL calculator for Ansys Fluent?

You can get an Excel-based CFL calculator by subscribing to the MR CFD newsletter. The calculator includes sections for incompressible and compressible flows and provides an instant calculation of the required timestep size.

What are the best practices for CFL in hypersonic simulations?

- Use the Density-Based Solver.

- Use Local Timestepping to get a good steady-state initial condition.

- Start with a low global Courant number, around 0.5 to 2.0, for the transient part.

- Ensure the flow and energy equations are solved in a coupled manner.

What’s your biggest challenge with transient simulations? Drop a comment below, and our team will respond with tailored advice. Top question wins a free 1-hour consulting session!

Comments (0)